CONTEXT

There are good reasons to consider the plausibility of data when it is asserted to mean something extraordinary. An example:

Someone with a dent in their car’s fender has a bit of blood and some brown fur in the dent. The car's owner claims they hit a deer the night before. Is that evidence plausible enough to believe that the claim is probably true? Probably for most people. But what if they said they hit a Bigfoot or a furry alien? Now is the evidence enough to be plausible? Would you ask for more evidence before believing the Bigfoot or alien claim is likely true?

The same thing applies to assertions of data from paranormal or psi research. Believers in explanations for supernatural, paranormal and psi phenomena argue that existing data proves that something is there, supernatural or not.

Psi phenomena are the aggregate of alleged parapsychological functions of the mind including extrasensory perception (ESP), precognition, and psychokinesis. Parapsychology is the study of mental phenomena which are inexplicable by orthodox scientific psychology and other knowledge. Such phenomena include telepathy, clairvoyance, and psychokinesis. Psychokinesis is the supposed ability of some people to move physical objects by mental effort alone.

ABOUT PLAUSIBILITY

I get e-mails, and my recent article on ESP research attracted a number of angry individuals who wanted to excoriate my closed minded “scientism”. I think people care so much about ESP and other psi and paranormal phenomena because it gets at the heart of their beliefs about reality – do we live in a purely naturalistic and mechanistic world, or do we live in a world where the supernatural exists? Further, in my experience while many people are happy to praise the virtue of faith (believing without knowing) in reality they desperately want there to be objective evidence for their beliefs. Meanwhile, I think it’s fair to say that a dedicated naturalist would find it disturbing if there really were convincing evidence that contradicts naturalism.Both sides have an out, as it were. Believers in a supernatural universe can always say that the supernatural by definition is not provable by science. One can only have faith. This is a rationalization that has the virtue of being true, if properly formulated and utilized. Naturalists can also say that if you have actual scientific evidence of an alleged paranormal phenomenon, then by definition it’s not paranormal. It just reflects a deeper reality and points in the direction of new science. Yeah!

Regardless of what you believe deep down about the ultimate nature of reality (and honestly, I couldn’t care less, as long as you don’t think you have the right to impose that view on others), the science is the science. Science follows methodological naturalism, and is agnostic toward the supernatural question. .... So you can have your faith, just don’t mess with science.ESP and psi believers become apoplectic when you mention scientific plausibility. In my experience, they have to misunderstand what it is and how it is used, no matter how many times or how many ways I explain it to them, in order to maintain their position. For example, I recently had an exchange where the e-mailer responded:Dr. Novella, your argumentation here is more reasonable, even if it still displays scientism. I’ll point to your statement, “This is especially true since they are proposing phenomena which are not consistent with the known laws of physics.” Here you’re making the known laws a determining factor for rejecting the prospect of the phenomena. The very point of the investigations is to see if something exists beyond the known laws. Again, the evidence is the authority. The known laws don’t disallow what isn’t known. You seem to think you’re making a very sound argument, all the while exhibiting pure scientism.

Of course, I said nothing of the kind, and no matter how many times I corrected this fallacy, he returned to it. The idea is that since science is trying to discover new things, that already established findings or laws don’t matter and can be comfortably ignored. “The evidence is the authority” – just like with alternative medicine. He pairs this with the straw man that plausibility is “a determining factor”.Here is how science actually works. First of all, science builds upon itself. We have to take into consideration prior knowledge, because that affects how we interpret new information. If, to give an extreme example to illustrate the point, I make an observation that seems to contradict 1000 prior observations, do we chuck out the prior observations? What is the probability that the 1 observation is wrong vs the 1000 observations?[There are some] people who claim that they have evidence for information going from the future to the past, or for information being transmitted from one brain to another without any detectable signal, and any known mechanism. The fact that these observations appear to contradict the known laws of physics is not “determinative”. But it is also not just a prior bias. It affects how rock solid [plausible] the evidence has to be before we conclude we have a genuine anomaly [inexplicable data or phenomenon] on our hands. In my opinion, this evidence (for ESP) is orders of magnitude too weak to conclude we have a genuine anomaly. The effect sizes are small, the researchers don’t have a great history for rigor, and the protocols cannot be reliably replicated. So we have relatively weak evidence being put up against rock solid laws of physics. It is not “scientism” to say that the evidence is not sufficient. And it is not scientific or logical to dismiss this dramatic lack of plausibility.

This exemplifies the ongoing disagreement between people who believe ESP and psi phenomena are real and mainstream science consensus that denies that ESP and psi are real. One of the believers, is researcher Daryl Bem. In 2011, Bem published an analysis of data from nine separate ESP experiments that showed that precognition is real. Precognition is knowing that an even will happen before it happens.

In 2015, Bem and others published a paper that analyzed 90 experiments from 33 laboratories and found that precognition is a real phenomenon. The statistical significance from the 90 experiment analysis was vey high, even higher than the significance that physicists demanded for belief in the discovery of the Higgs boson in 2012. For context, the FDA requires statistical significance of there being a 5% (1 chance in 20) or less chance of the data for a new drug being a statistical fluke. That is usually expressed as p ≤ 0.05 (p means probability of a fluke). The lower the p number, the smaller chance there is of data being a fluke or an anomaly.

The significance of Bem's 90 experiment analysis was p = 1.2 × 10-10 or p = 0.00000000012. In other words, the chance of the data being a fluke is extremely low, 1.2 in 10 billion. Despite that, mainstream science still rejects psi phenomena as real, citing the implausibility of precognition in view of the laws of the universe. Mainstream science looks for explanations that do not violate the any law of the universe. Here, the violation is knowledge of a future event flowing backward in time and being accurately sensed by the human brain-mind before the event occurs.

An expert rejects psi phenomena

One expert on Bem's work expresses a major concern about the entire scientific enterprise in view of Bem's analysis. E.J. Wagenmakers writes:

James Randi, magician and scientific skeptic, has compared those who believe in the paranormal to “unsinkable rubber ducks”: after a particular claim has been thoroughly debunked, the ducks submerge, only to resurface again a little later to put forward similar claims.

Several of my colleagues have browsed Bem's meta-analysis and have asked for my opinion. Surely, they say, the statistical evidence is overwhelming, regardless of whether you compute a p-value or a Bayes factor. Have you not changed your opinion? This is a legitimate question, one which I will try and answer below by showing you my review of an earlier version of the Bem et al. manuscript.

I agree with the proponents of precognition on one crucial point: their work is important and should not be ignored. In my opinion, the work on precognition shows in dramatic fashion that our current methods for quantifying empirical knowledge are insufficiently strict. If Bem and colleagues can use a meta-analysis to demonstrate the presence of precognition, what should we conclude from a meta-analysis on other, more plausible phenomena?

Disclaimer: the authors [Bem et al] have revised their manuscript since I reviewed it, and they are likely to revise their manuscript again in the future. However, my main worries call into question the validity of the enterprise as a whole.I urge the authors to convince themselves of the absence of psi and try and replicate one of Bem's experiment in a purely confirmatory setting, with a preregistered analysis protocol. When they monitor the Bayes factor they will, as N grows large, obtain massive evidence in favor of the truth. One good, preregistered experiment is worth a thousand experiments where the results are based on cherry-picking. To indicate that cherry-picking is a problem, I have never seen a preregistered experiment that monitored the Bayes factor and ended up supporting psi. Never.

Research on extra-sensory perception or psi is contentious and highly polarized. On the one hand, its proponents believe that evidence for psi is overwhelming, and they support their case with a seemingly impressive series of experiments and meta-analyses. On the other hand, psi skeptics believe that the phenomenon does not exist, and the claimed statistical support is entirely spurious. We are firmly in the camp of the skeptics. However, the main goal of this chapter is not to single out and critique individual experiments on psi. Instead, we wish to highlight the many positive consequences that psi research has had on more traditional empirical research, an influence that we hope and expect will continue in the future.

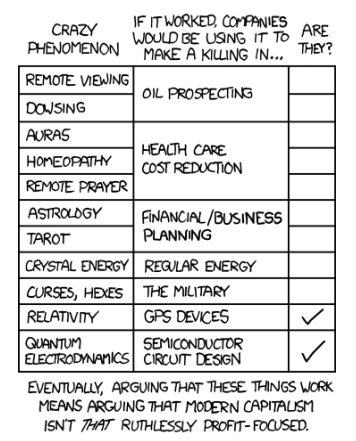

It is evident that even the smallest psi effects are worth millions if applied in games of chance. An online betting facility that requires the gambler to predict, say, whether a picture will appear at the left or on right of the screen should go bankrupt as soon as extraverted females [??] are allowed to predict the location of erotic pictures (we are happily prepared to invest in such a casino). If psi is demonstrably effective in generating cash, it would quickly be accepted in the pantheon of scientifically credible phenomena.

No comments:

Post a Comment