Context

Reasoned Politics is a 2022 book written for a general audience by a young Danish author, Magnus Vinding. Vinding has an undergraduate degree in math and some undergraduate study in areas including psychology, philosophy, and the history of science. He relies heavily on cognitive biology, social behavior and moral philosophy of politics to argue for politics that is more rational and reasoned than it is now. His main interest now is in reducing suffering and the moral reasoning behind of that goal. Vinding is not an academic. As far as I can tell, he has authored no peer-reviewed papers in the science literature. He founded and apparently works at the Center for Reducing Suffering, presumably in Denmark. His book is very easy to read. It is available online in pdf format.

If I had written a book, I would hope it would be close to Reasoned Politics. What Vinding calls reasoned politics, I call pragmatic rationalism. The two are nearly identical. In my communications with him, he and I both draw on the same sources of influence on politics, human cognitive biology, social behavior and moral philosophy. He sees the same major problem with reasoned politics (my pragmatic rationalism) that I see. Specifically, reasoned politics cannot stand alone because rationalism alone does not have the personal and social glue that most humans (~95% ?) need to be drawn in. It's impossible to build a big cohesive tribe based on rationalism alone, which is often quite uncomfortable psychologically, socially or both.

Magnus Vinding

Book review

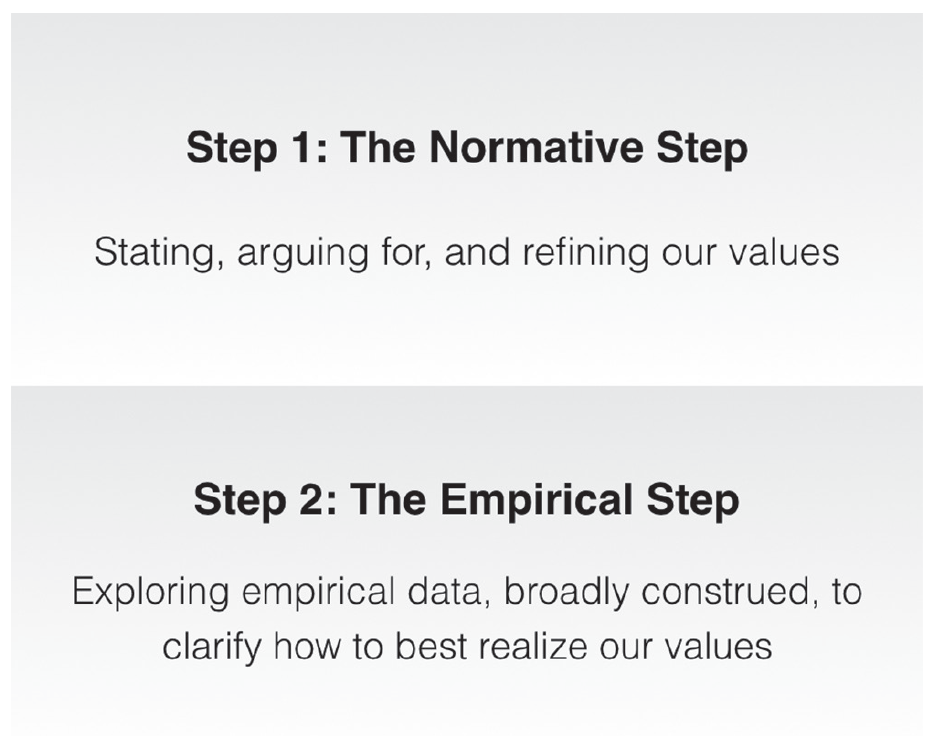

Broken politics: Reasoned Politics starts with a description of broken politics and a two-step protocol for doing it better:

Politics is broken. To say that this is a cliché has itself become a cliché. But it is true nonetheless. Empty rhetoric, deceptive spin, and appeals to the lowest common denominator. These are standard premises in politics that we seem stuck with, and which many of us shake our heads at in disappointment.

The good news is that we have compelling reasons to think that we can do better. And it is critical that we do so, as our political decisions arguably represent the most consequential decisions of all, serving like a linchpin of human decision-making that constrains and influences just about every choice we make.

The two-step protocol is actually three steps: Vinding's two-step protocol is simple:

A problem with mainstream political discourse is that there is a striking lack of distinction between normative and empirical matters. That is, we fail to distinguish ethical values on the one hand, and factual questions about how we can best realize such values on the other, which in turn causes great confusion. And predictably so. After all, the distinction between normative and empirical issues is standard within moral and political philosophy, where it is considered indispensable for clear thinking.

If that feels familiar to some regulars here, it should. My pragmatic rationalism envisions a two-step protocol, first the empirical step, second the normative step. This is the only significant difference between Vinding's brand of politics and mine.

I put the empirical first specifically because it tends to be less emotion and bias-provoking than thinking about one's morals. I pointed this reversal of order out to Vinding and he sticks with his order of things, but he then raised the possibility of a third step, being aware of common biases, which he termed step 0. He and I both think that self-awareness of personal biases and group or tribe loyalties are a necessary predicate for doing reasoned politics. So, three steps arguably is needed, with self-awareness training part of the protocol being the first step.

The point of step three is simple. If a person denies that they are biased or influenced by group or tribe loyalty, they've already positioned themselves to likely fail at reasoned politics and unknowingly default back to broken politics.

Moral reasoning, cognitive biases & virtue signaling to the tribe: Vinding then marches through cognitive biology, social influences on moral reasoning and the main unconscious biases that distort our perceptions of reality and facts and how we think about what we think we see. The point is to raise self-awareness of how powerful but subtle people's main biases are on both perceiving things and thinking about them. Some quotes from the book are in order.

- In their book Democracy for Realists [my book review is here], political scientists Christopher Achen and Larry Bartels review a large literature that consistently shows that voters mostly vote based on their group membership and identity rather than their economic self-interest (Achen & Bartels, 2016). This contrasts with what Achen and Bartels call the “folk theory” of democracy, a more rationalistic view according to which voters primarily vote based on their individual policy preferences — a view that turns out to be mostly false (Achen & Bartels, 2016, ch. 8-9).

- It is well-documented that the human mind is subject to confirmation bias: a tendency to seek out and recall information that confirms our pre-existing beliefs while disregarding information that challenges these beliefs (Plous, 1993, pp. 233-234). Closely related is the phenomenon of motivated reasoning, which is when we seek to justify a desired conclusion rather than following the evidence where it leads (Kunda, 1990). It hardly needs stating that confirmation bias and motivated reasoning are rampant in politics (as indeed implied by Haidt’s social intuitionist model).

- Voters tend to be ignorant about politics. In fact, this has been characterized as one of the most robust findings in political science (Bartels, 1996; Brennan, 2016, ch. 2). And voters are not just wrong in small ways on insignificant matters, but in big ways on major issues. In the words of political scientist Jeffrey Friedman, “the public is far more ignorant than academic and journalistic observers of the public realize” (Friedman, 2006b, p. v). .... A relevant phenomenon in this context is the “illusion of explanatory depth” — the widespread illusion of believing that we understand aspects of the world in much greater detail than we in fact do.

- To be clear, the point here is not that our intuitions should be wholly disregarded. After all, our intuitions often do carry a lot of wisdom, sometimes even encapsulating centuries of hard-won cultural moral progress. .... But the point is that we do not have to go with the very first intuition that eagerly announces itself and tries to dictate our judgment.

- .... political scientists have deemed group attachments [tribalism] “the most important factor” in determining people’s political judgments (Achen & Bartels, 2016, p. 232). This is at odds with the more common and more flattering view of ourselves that says that our political judgments are primarily determined by our individual reasoning — a picture that assigns little importance to our group affiliations, if any at all. .... And as is true of motivated reasoning in general, our drive to signal group loyalty is rarely fully transparent to ourselves, in that it rarely comes with any indication that it serves the purpose of loyalty signaling. Both individually and collectively, we have little clue of the extent to which group loyalty motivates our political behavior (Achen & Bartels, 2016, ch. 10; Simler & Hanson, 2018, ch. 5, ch. 16).

Reasoned politics or broken politics?

Vinding's book concludes with various thoughts about the difficulty of people doing reasoned politics and our unconscious tendency to do broken politics.

- Lastly, a significant impediment to the two-step ideal is that the true epistemic brokenness of the human mind, especially in the realm of politics, is hardly something welcome or flattering for anyone to hear about. .... In particular, it may be difficult for us to recognize that much of our epistemic brokenness is a direct product of our social and coalitional nature itself (cf. Simler, 2016; Tooby, 2017). After all, we tend to prize our social peers and coalitions, so it might be especially inconvenient to admit that they are often the greatest source of our epistemic brokenness — e.g. due to the seductive drive to signal our loyalties to them and to use beliefs as mediators of bonding, which often comes at a high cost to our epistemic integrity (Simler, 2016).

It is clear from Vinding's, book that American society and political rhetoric is currently inimical to the rise of reasoned politics. For now, reasoned politics will remain an academic curiosity instead of the potent political force that America and the rest of the world desperately needs right now.

No comments:

Post a Comment