If I am not self-deluded, there is a slowly growing awareness among some of the cognoscenti in the MSM (mainstream media) about the two core sources of politics that I have been harping on for the last ~26 years. What sources? Human cognitive biology and human social behavior. I do believe that some people are actually starting to get it. Is that possible? Nah, can't be. Right? well, maybe not right.

A fascinating NYT opinion (not paywalled) makes some very cognitive biology-centered arguments about language and how labels influence perceptions of reality (how reality is framed) and how we think about what we think we see:

To Put It Bluntly

If Donald Trump ends up serving a term in prison (there’s still hope!), I’d relish the chance to refer to him as an ex-con. Like “felon,” the brute force of the term, with its hard-boiled matter-of-factness, would be extremely satisfying.

But the very power of that label has made it practically taboo. In its place, even federal prosecutors have adopted phrases like “justice involved” or “justice impacted” to describe those convicted of crimes — as if we could reform the entire criminal justice system simply by using new words.

Much ado has been made of euphemism inflation, the ceaseless efforts to reform the English language toward desired social or political ends.Let’s return to the old “ex-con.” .... Even “former prisoner” and “formerly incarcerated person” have grown passé. But “justice involved” and “justice impacted” go further yet. They not only avoid stigma, they also remove the implication of responsibility altogether, as if the crime were something that happened to the criminal rather than an act he committed himself.The right euphemism not only removes blame, it also reassigns it. Thus, “prisons” become the “carceral system” or part of the “carceral state,” which suggests that the act of imprisoning people may itself be the crime. The implied question is: What gives the state a right to put people away?One major goal of lexical reform is to humanize and dignify the person behind a simple label. This is exemplified by what The Associated Press calls “person-first” language, recommended in its latest guidebook, issued in May, when referring to anyone implicated in the criminal justice system, avoiding terms like “inmate” and “juvenile.”Another example is the word “slave,” which suggests a totalizing condition, while the increasingly preferred “enslaved person” emphasizes that the person is someone upon whom slavery (or “enslavement”) has been imposed.Not all these rephrasings are necessarily downgrades, or even wrong. There is inarguably a power, sometimes a necessary one, in reconstituting terms, especially when they refer to human beings. As Toni Morrison once explained, “The definers want the power to name. And the defined are now taking that power away from them.”Many of these changes seem neutral on the face of it. The replacement of “homeless” with “unhoused” at first glance seems like a superfluous switcheroo. But key to the change is the implication that the government has failed to provide a home, not that someone has lost one. Similarly, “poor” neighborhoods become “under-resourced communities.” And truancy, which feels like an accusation of juvenile delinquency, instead becomes “absenteeism,” which humbly suggests a box left unticked on the attendance list, more the fault of the school than the student.Language has always driven and reflected societal change. In Orwell’s time, vague language was used by the powerful to defend or obscure brutality (e.g., British rule in India, Stalin’s purges, Soviet deportations).

This tendency still exists in political language (see “enhanced interrogation”). But today’s vague language is more often used as a means to ward off bad things so we don’t have to deal with harsh reality. Euphemistic language becomes a kind of wishcasting, and perhaps even a way of avoiding — or covering up a lack of — more substantive reform.At a time when words are frequently treated as tools of oppression or means of resistance, charged with causing harm or spreading misinformation, we’ve all started watching what we say. But for language to remain an effective way to communicate intent and meaning, we should consider the reasons — beyond kindness or sensitivity — behind our euphemisms. Some words are brutal for a reason, and sometimes we need to deliver a pure blunt force.

In the recent Harris vs DJT debate, I was looking for more blunt force from Harris than she delivered. That led me to think her debate performance was mediocre. Apparently, my assessment was wrong and her performance was better than mediocre.

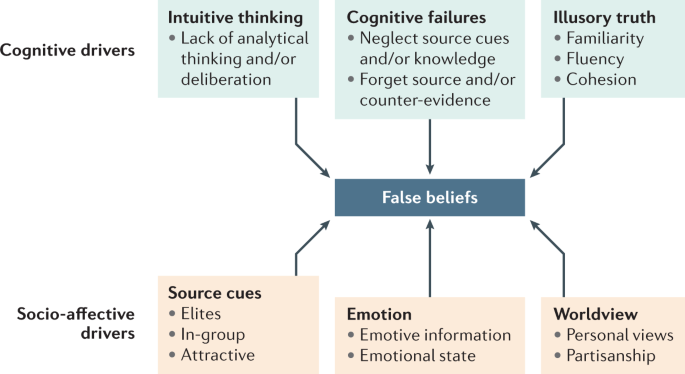

This opinion piece raises the issue of political correctness. Professional political propagandists and marketers have been aware of the power of labels for decades. For example relabeling the estate tax as the "death tax" was coined in the 1940s, but it didn't gain traction until the 1990s. This propaganda tactic is old, not new. The death tax label effectively reframed the issue in a negative way that wealthy people wanted. In essence, radical right authoritarians invented their own political correctness (PC) and treated it as the right way to see things as opposed to how pro-democracy.

That is why, at least for a while, America's authoritarian radical right wealth and power movement was so critical of PC. PC was contentious because it took power from authoritarian definers and transferred it to the defined. The MSM seems to be waking up to this.

That raised a question -- attacks on PC seem to be less common, but why?:

Q: Why aren't American radical right authoritarians attacking political correctness as much as they did some years ago?A: The perception that American radical right authoritarians are not attacking political correctness as much as they did in recent years may not be entirely accurate. However, there are some factors that could contribute to a shift in focus or messaging:Evolving Rhetoric and PrioritiesChanging Targets: Rather than directly attacking "political correctness," radical right groups may have shifted their focus to more specific issues like critical race theory, gender identity, or immigration policies.

Mainstreaming of Anti-PC Sentiment: Some anti-political correctness views have become more mainstream within conservative circles, potentially reducing the need for radical groups to emphasize this particular issue.Political and Social ClimatePost-Trump Era: During the Trump presidency, attacks on political correctness were a central theme. In the post-Trump era, radical right groups may be recalibrating their messaging strategies.Social Media Dynamics: Changes in social media platforms' policies and algorithms may have affected the visibility of radical right content, including anti-PC messaging.

It's important to note that while the specific language or frequency of attacks on political correctness may have evolved, the underlying sentiments often remain present in different forms within radical right discourse. The apparent reduction in attacks on political correctness could be more a matter of changing tactics and rhetoric rather than a fundamental shift in ideology.

No comments:

Post a Comment