The mean lifetime, τ = ħ/Γ, of the (positive) muon is (2.1969811±0.0000022) μs (microsecond). Certain neutrino-less decay modes are kinematically allowed but are, for all practical purposes, forbidden in the Standard Model, even given that neutrinos have mass and oscillate. Examples forbidden by lepton flavor conservation are:

μ−

→

e−

+

γ

and

μ−

→

e−

+

e+

+

e−

.

Experiments with particles known as muons suggest that there are forms of matter and energy vital to the nature and evolution of the cosmos that are not yet known to science.

Evidence is mounting that a tiny subatomic particle seems to be disobeying the known laws of physics, scientists announced on Wednesday, a finding that would open a vast and tantalizing hole in our understanding of the universe.

The result, physicists say, suggests that there are forms of matter and energy vital to the nature and evolution of the cosmos that are not yet known to science. The new work, they said, could eventually lead to breakthroughs more dramatic than the heralded discovery in 2012 of the Higgs boson, a particle that imbues other particles with mass.

“This is our Mars rover landing moment,” said Chris Polly, a physicist at the Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory, or Fermilab, in Batavia, Ill., who has been working toward this finding for most of his career. Evidence is mounting that a tiny subatomic particle seems to be disobeying the known laws of physics, scientists announced on Wednesday, a finding that would open a vast and tantalizing hole in our understanding of the universe.

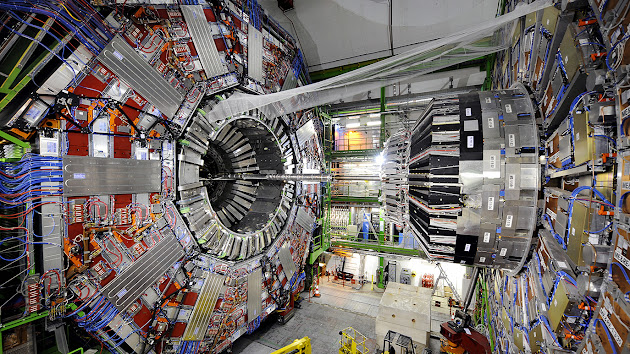

The particle célèbre is the muon, which is akin to an electron but far heavier, and is an integral element of the cosmos. Dr. Polly and his colleagues — an international team of 200 physicists from seven countries — found that muons did not behave as predicted when shot through an intense magnetic field at Fermilab.

The aberrant behavior poses a firm challenge to the Standard Model, the suite of equations that enumerates the fundamental particles in the universe (17, at last count) and how they interact.

“This is strong evidence that the muon is sensitive to something that is not in our best theory,” said Renee Fatemi, a physicist at the University of Kentucky.

The results, the first from an experiment called Muon g-2, agreed with similar experiments at the Brookhaven National Laboratory in 2001 that have teased physicists ever since. “After 20 years of people wondering about this mystery from Brookhaven, the headline of any news here is that we confirmed the Brookhaven experimental results,” Dr. Polly said.

The team had to accommodate another wrinkle. To avoid human bias — and to prevent any fudging — the experimenters engaged in a practice, called blinding, that is common to big experiments. In this case, the master clock that keeps track of the muons’ wobble had been set to a rate unknown to the researchers. The figure was sealed in envelopes that were locked in the offices at Fermilab and the University of Washington in Seattle.

In a ceremony on Feb. 25 that was recorded on video and watched around the world on Zoom, Dr. Polly opened the Fermilab envelope and David Hertzog from the University of Washington opened the Seattle envelope. The number inside was entered into a spreadsheet, providing a key to all the data, and the result popped out to a chorus of wows.

“That really led to a really exciting moment, because nobody on the collaboration knew the answer until the same moment,” said Saskia Charity, a Fermilab postdoctoral fellow who has been working remotely from Liverpool, England, during the pandemic.

There was pride that they had managed to perform such a hard measurement, and then joy that the results matched those from Brookhaven.

“This seems to be a confirmation that Brookhaven was not a fluke,” Dr. Carena, the theorist, said. “They have a real chance to break the Standard Model.”