Context

1. I've now progressed in my thinking about politics that, assuming I can do it and there is some supporting data, most every politics OP I post should be linked to cognitive or social science in some way. The reason is simple: Cognitive and social science describe politics and the human condition better than any political partisan, special interest, blowhard, crook, liar, demagogue, political or religious ideologue or murderer ever would. I am sure there are a few or some major business people, politicians, etc., who are significantly, mostly or completely exceptions to that blanket condemnation. Well, pretty sure. I hope.

2. Over my lifetime to date, I've come to believe that for modern times, men in power have been and still are probably (~85% personal confidence) significantly worse than women in power would be in terms of acceptance of facts and true truths, rational reasoning, governing, reasonable empathy and civility, honesty** and exercise of soft power (non-war and /or mass slaughter) effectiveness. Exercise of hard power, i.e., the military and kinetic force, seems to come way too easy to men. The caveat on that belief is that I am not a historian and thus no expert.

3. Is there a historian in the house? I really need one right now.

** No, reasonable empathy, civility or honesty does not mean anything close to gullibility, stupidity or any other weakness. IMO, reasonable (not stupid) empathy, civility and honesty are strengths, not weaknesses and when circumstances merit, they need to be mostly or completely withdrawn.

Bad boys

An article my home town newspaper the San Diego Union Tribune published today was interesting. The article, Why more men aren't wearing masks -- and how to change that, reported data indicating that men are less prone to wear face masks than women. Duh. Observing unmasked men in public compared to women and children with their moms inspired Hélène Barcelo of the Mathematical Science Research Institute in Berkeley, to look closely. A study by Barcelo and Valerio Capraro of London’s Middlesex University generated data indicating that men are less likely than women to wear face covering.The SDUT writes:

“Posted online in mid-May, the resulting study of 2,459 U.S. participants, “The Effect of Messaging and Gender on Intentions to Wear a Face Covering to Slow Down COVID-19 Transmission,” offers an interesting glimpse into why some men resist the call to cover up — and provides some clues as to how to influence that behavior. In addition to finding that men are less inclined to wear a face mask, the study found that men are less likely than women to believe they will be seriously affected by the coronavirus.

Further, it found a big difference between men and women when it came to the self-reported negative emotions that come with that simple strip of fabric across the face.

As study co-author Capraro explained, “We asked [participants to rank] on a scale of one to 10 how much they agreed with five different statements: ‘Wearing a face covering is cool,’ ‘Wearing a face covering is not cool,’ ‘Wearing a face covering is shameful,’ ‘Wearing a face covering is a sign of weakness’ and ‘The stigma attached to wearing a face covering is preventing me from wearing one as often as I should.’

“The two statements that showed the biggest difference between men and women,” Capraro said, “were, ‘Wearing a face covering is a sign of weakness’ and ‘The stigma attached to wearing a face covering is preventing me from wearing one as often as I should.’”To reorient the male mind on this point, the researchers suggest these:

1. Emphasize the benefit to community over than family, country or self. That tactic appeared to be the biggest motivator for men. (Germaine: Wot? Over family? No wonder we're on the road to hell. -- See, that exemplifies why I think women are better suited for rule than men.)

SDUT quotes a researcher o this point: “One of my areas of research is in benevolent sexism. So one way to rebrand this is instead of [making it about] protecting yourself, make it about protecting other people. [Make it about being] paternalistic and chivalrous. You’re saying, ‘I’m protecting the weak, the elderly, [and] I’m being a hero.”

2. “According to Alex Navarro, assistant director of the Center for the History of Medicine at the University of Michigan and one of the editors-in-chief of the American Influenza Epidemic of 1918-1919: A Digital Encyclopedia, an overt appeal to patriotism was used to encourage mask-wearing in the early stages of the Spanish flu epidemic as the country was still fighting World War I.”

3. SDUT writes:

I don't know how anyone else reads that, but I read it like this: (whining voice) I'm a big stud. You've gotta listen to and obey me.

I'm not impressed with that. The only question in my mind is how accurate it is or is not. (I need to do more research on this point, so CAVEAT)

2. “According to Alex Navarro, assistant director of the Center for the History of Medicine at the University of Michigan and one of the editors-in-chief of the American Influenza Epidemic of 1918-1919: A Digital Encyclopedia, an overt appeal to patriotism was used to encourage mask-wearing in the early stages of the Spanish flu epidemic as the country was still fighting World War I.”

Apparently, this appeals to most men more than facts and reason

-- what a stud!

3. SDUT writes:

“If stereotypical masculine behavior is part of the problem, might it be part of the solution? Could some of the traits traditionally associated with manliness be Trojan Horsed to increase the number of masked men? Glick, who back in April penned a piece for Scientific American titled “Masks and Emasculation: Why Some Men Refuse to Take Safety Precautions,” thinks the approach might work.

‘Of course you’d be playing into this kind of masculinity,’ Glick said, ‘but I think tough-looking masks — MAGA masks, camouflage[-print masks], [masks printed with] shark teeth — might. They wear masks in wrestling, right? And what about superheroes and villains?’”

That speaks for itself.

4. And there's this about the power of humor with men:

“‘I think [humor] definitely could work,’ he said. ‘A lot of men communicate this way. They have serious conversations but in humorous ways because [they] can’t fully own it so [they] joke about it. For example, guys in the locker room might be talking about the difficulties in [their] marriages but by joking about it. It’s kind of a code they use to communicate, to admit they’re having a hard time.’

Englar-Carlson said he wasn’t exactly sure what a humorous messaging campaign around mask-wearing might look like, but with Glick’s comment about wrestlers, superheroes and villains echoing in my ears, I floated one possibility: a PSA featuring Darth Vader, Bane from “The Dark Knight Rises” and a cadre of Lucha Libre wrestlers playing it tough while urging guys to put on their own masks.”

Is it me, or do many or most men look mentally weak? You can't present them with reality so you have to deflect, cajole, pull rabbits out of hats and otherwise massage fragile egos.

The SDUT article continues in this vein.

Questions:

1. Does this reasonably indicate that men as leaders are too wuss in terms of self-confidence or mental power and compensate with unjustified violence, including not wearing a facemask in the face of COVID-19, and war too often? Or is just one thing insufficient to draw such a sweeping conclusion?

2. Are men’s egos really as fragile as I think this article reasonably conveys?

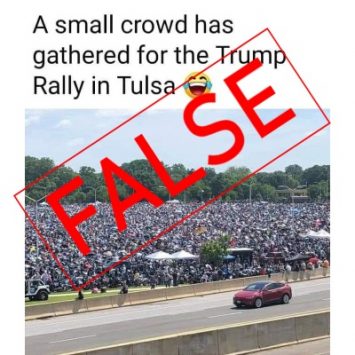

Trump Rally in Tulsa

Trump Rally in Tulsa