Trump Allies Continue Legal Drive to Erase His Loss, Stoking Election Doubts

Fifteen months after they tried and failed to overturn the 2020 election, the same group of lawyers and associates is continuing efforts to “decertify” the vote, feeding a false narrative.In statehouses and courtrooms across the country, as well as on right-wing news outlets, allies of Mr. Trump — including the lawyer John Eastman — are pressing for states to pass resolutions rescinding Electoral College votes for President Biden and to bring lawsuits that seek to prove baseless claims of large-scale voter fraud. Some of those allies are casting their work as a precursor to reinstating the former president.

The efforts have failed to change any statewide outcomes or uncover mass election fraud. Legal experts dismiss them as preposterous, noting that there is no plausible scenario under the Constitution for returning Mr. Trump to office.The efforts have fed a cottage industry of podcasts and television appearances centered around not only false claims of widespread election fraud in 2020, but the notion that the results can still be altered after the fact — and Mr. Trump returned to power, an idea that he continues to push privately as he looks toward a probable re-election run in 2024.“At the moment, there is no other way to say it: This is the clearest and most present danger to our democracy,” said J. Michael Luttig, a leading conservative lawyer and former appeals court judge, for whom Mr. Eastman clerked and whom President George W. Bush considered as a nominee to be the chief justice of the United States. “Trump and his supporters in Congress and in the states are preparing now to lay the groundwork to overturn the election in 2024 were Trump, or his designee, to lose the vote for the presidency.”

Pragmatic politics focused on the public interest for those uncomfortable with America's two-party system and its way of doing politics. Considering the interface of politics with psychology, cognitive biology, social behavior, morality and history.

Etiquette

Wednesday, April 20, 2022

Republican attacks on democracy continue to advance the cause of neo-fascism

Tuesday, April 19, 2022

The Most Popular Politicians are Moderates

A really obvious point that will probably make some people mad

Here are two basic facts about politics:

Figuring out how to win elections and be popular once in office is very important.

Doing the political science research necessary to demonstrate the best way to do that is really hard.

There are a few reasons for this second point. First, data quality in politics is often bad. Polling is hard (and getting harder) so figuring out what voters actually want is tricky. Second, you can’t really run randomized control trials of different political strategies. Parties want to win, and they’re not inclined to assign each of their 435 congressional candidates a slightly different strategy to produce the kind of data that would make it past peer review. Third, the effect size of any given political maneuver is generally pretty small. So without randomization and large sample sizes, it’s hard to know whether a politician's victory should be attributed to their policy ideas, the national environment, or local events.

In this situation, I think it’s useful to zoom out for a second, and to look to the states to try to find some broad patterns of what seems to work for politicians and what doesn’t.

The most popular governors and senators

Morning Consult regularly publishes approval ratings for every American governor and senator. But the numbers in themselves aren’t that useful. The most popular governor in the country right now is Mark Gordon of Wyoming, who boasts a 69% approval rating. But is Gordon popular because his policies and messaging are great, or because he’s a generic Republican in a state that loves Republicans?

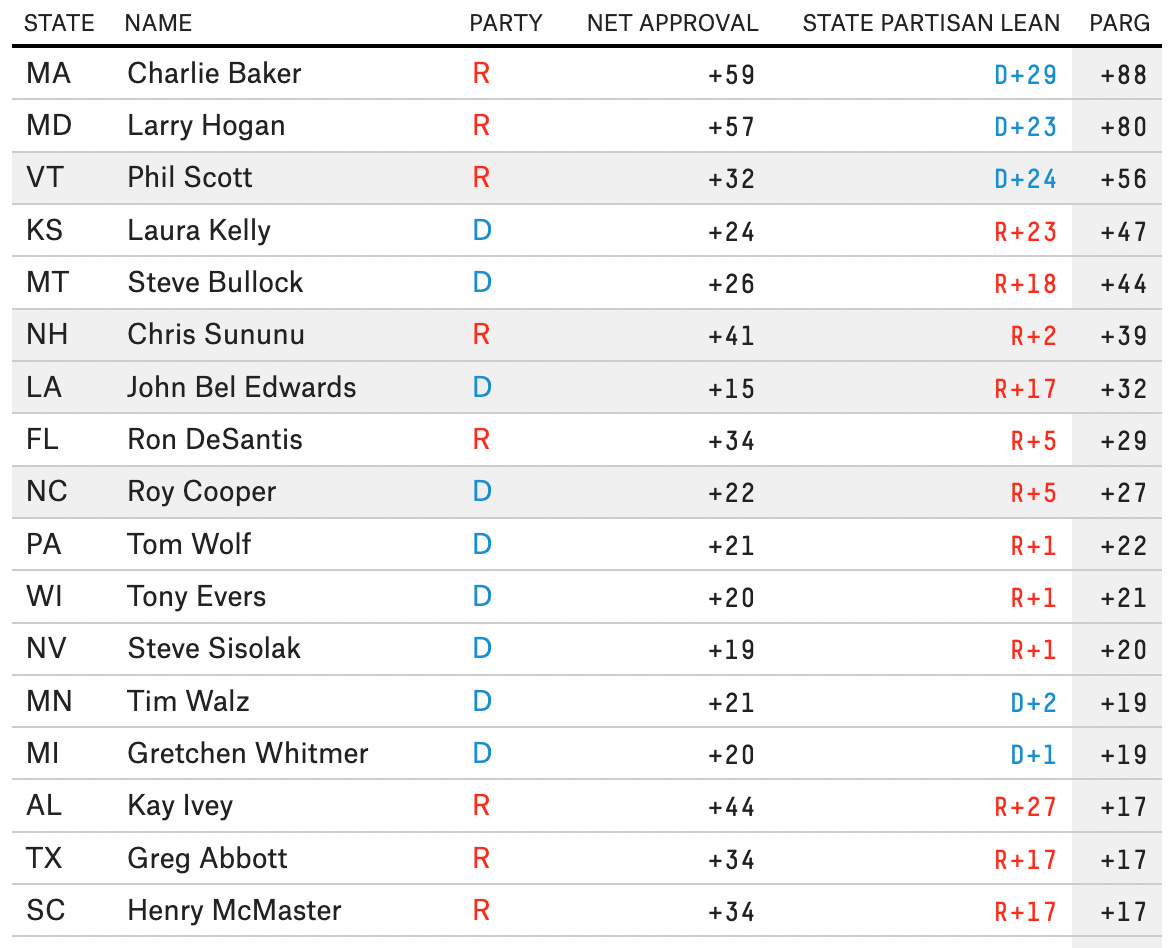

It’s much more instructive to look at popularity relative to the partisan lean of a state. In 2019, FiveThiryEight’s Nathaniel Rakich put together a ranking of the most popular governors and senators “above replacement.”1 Here’s what the top 15 look like for governors:

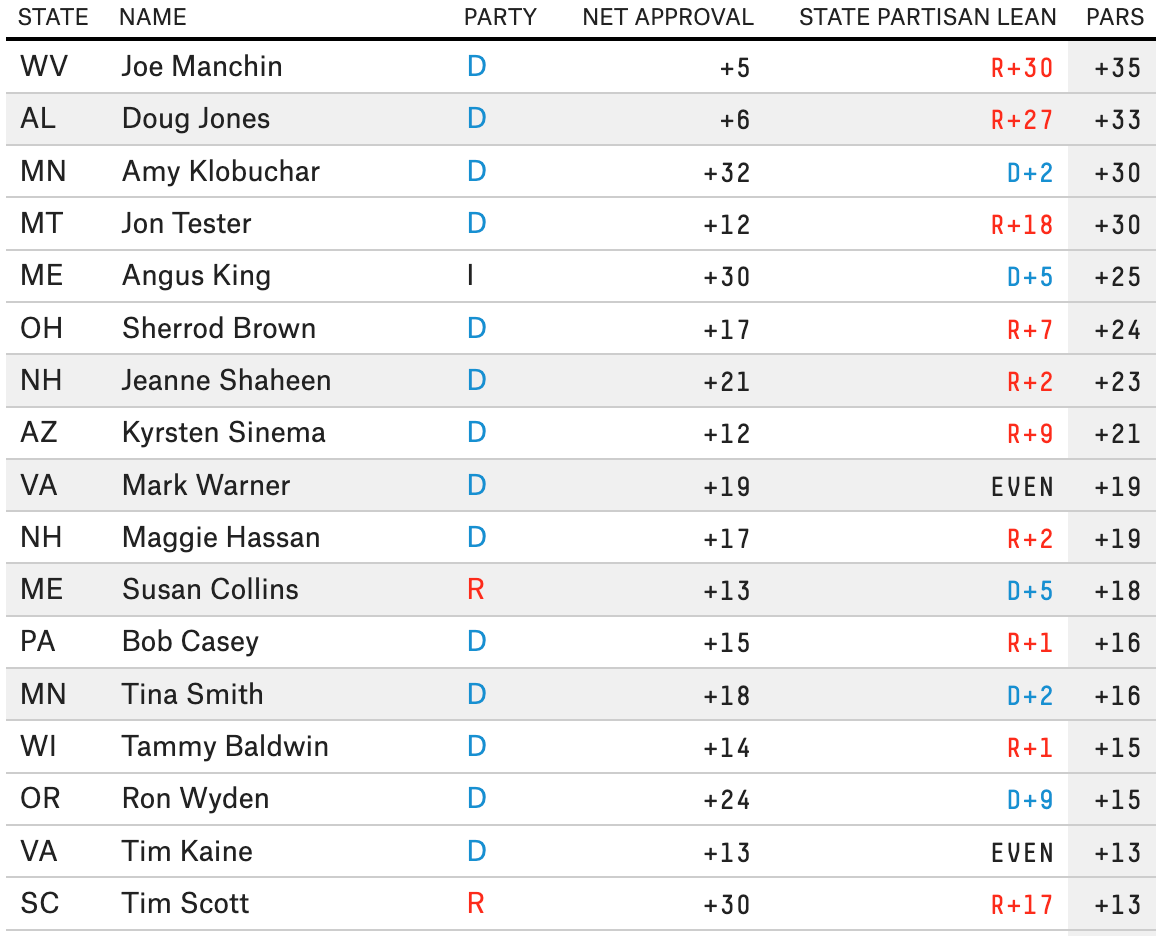

And here’s the top 15 for senators:

Looking at these lists cuts through a lot of the noise surrounding debates on ideological positioning and political success. The story they tell is clear. Overwhelmingly, the most popular governors tend to be moderates – and specifically, moderates who act as a counterbalance to their state’s more extreme legislatures. As for senators, look at the names at the top of the list. Manchin. Klobuchar. Jones. Tester. Collins. Warner. Again, they tend to be moderates by brand, who avoid taking radical stances on policy, and cultivate a reputation for independence by bucking their party at times.2

Looking at popularity above replacement doesn’t “prove” anything about political strategy. There could be confounding variables – maybe the popularity of moderates is just a coincidence, and has nothing to do with their ideological posturing. Correlation isn’t causation, etc etc.

But in the words of XKCD’s Randall Munroe, “Correlation doesn't imply causation, but it does waggle its eyebrows suggestively and gesture furtively while mouthing 'look over there.'” The simplest, Occam’s razor style explanation is that there is a real connection here – one we should take seriously.

I think that the clear over-representation of moderates at the top of these two lists should strongly influence how we think about political strategy. At the very least, it should convey a sense of what works and what doesn’t in electoral politics. That’s not at all to say politicians should embrace centrism at every turn. But I think you should probably have a pretty strong prior that, all else equal, having a reputation for moderation will help you win elections, especially if you’re seen as independent of your party.

Writing it out like that, it almost seems so banal and obvious as to be not worth saying. But much of the progressive wing of the Democratic party has decided to ignore what was in previous eras a cornerstone of political conventional wisdom, so I think it’s useful to say anyway.

It’s not ideal that this data is three years old, but Morning Consult stopped updating their governor and senator approval rating tracking, and I didn’t have time this week to recreate FiveThirtyEight’s graphic myself. Overall, I don’t think much has changed since 2019. Joe Manchin still tops the senators list, with a 59% (!) approval rating in a state Biden got 30% of the vote in. I think Larry Hogan now tops the governors list, with a +52 approval rating in a state Biden won by 33%.

There’s one notable senator, who despite being far from a Manchin-esque moderate, nevertheless manages to be far more popular than his state’s partisanship would seem to dictate: Sherrod Brown. I don’t think it’s a coincidence that he’s also one of the senators who most emphasizes kitchen table economic issues, and tends to avoid making progressive social stances a major part of his brand.

Democrats are sleepwalking into a Senate disaster

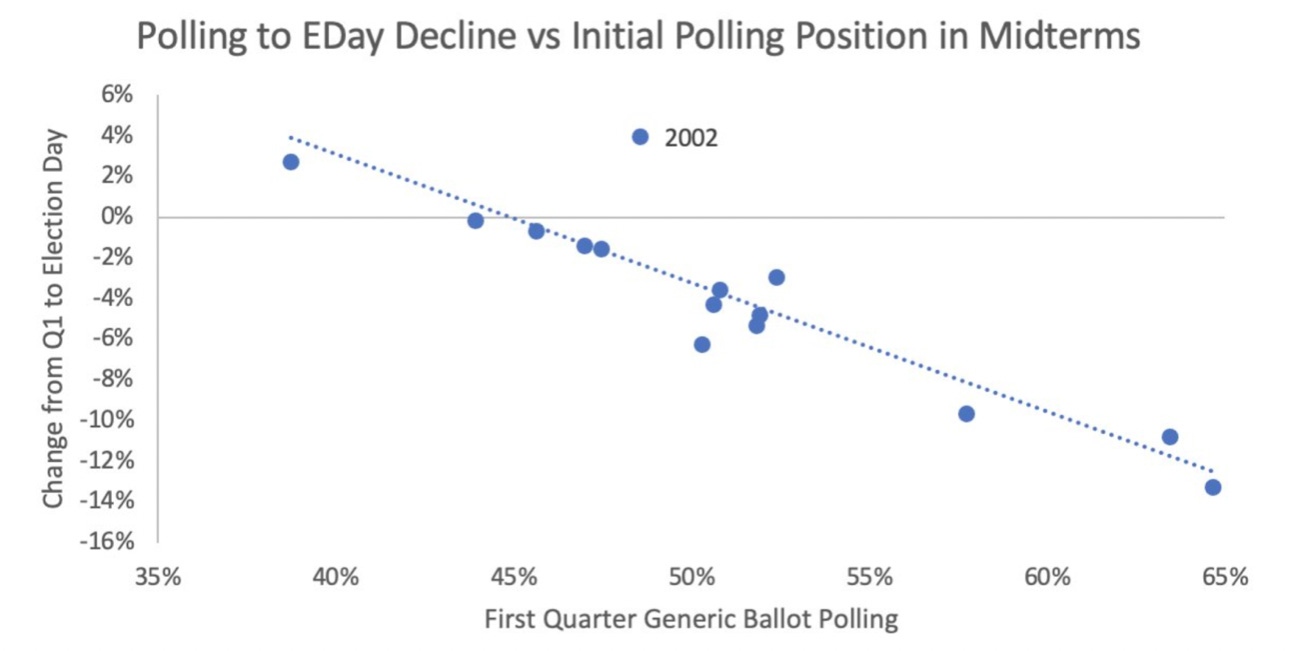

Traditionally, the President’s party averages roughly 47.5% of the two-party vote in midterms. Right now, in FiveThirtyEight's average of public polls, Democrats are polling at 48.7%. However, the President’s party also tends to decline in standing as the midterms approach, as the graph below shows (you can read more about the historical evidence for this decline here). The one clear exception involved the 9/11 terrorist attacks and does not offer Joe Biden grounds for optimism.

Additionally, polls have been biased towards Democrats in two of the last three cycles, and there is reason to think this bias will persist. The current 48.7% polling average may well be an overestimation.

Between those two factors, it’s reasonable to assume that Democrats are looking at a vote share between 47% and 48.5% this cycle. This means Republicans will probably win the generic ballot by between three and six percent, and the median scenario is probably Republicans winning by around 4.5%. Since Joe Biden won by 4.5% in 2020, this would mean that the national environment has shifted 9 percentage points to the right.

Assume, for a moment, that there is zero ticket-splitting, and this swing is uniform across all elections. This would mean any Democrat in a state that Biden won by less than 9% will probably lose. That includes:

Mark Kelly in Arizona (Biden +0.3)

Raphael Warnock in Georgia (Biden +0.2)

Catherine Cortez-Masto in Nevada (Biden +2.4)

Maggie Hassan in New Hampshire (Biden +7.4)

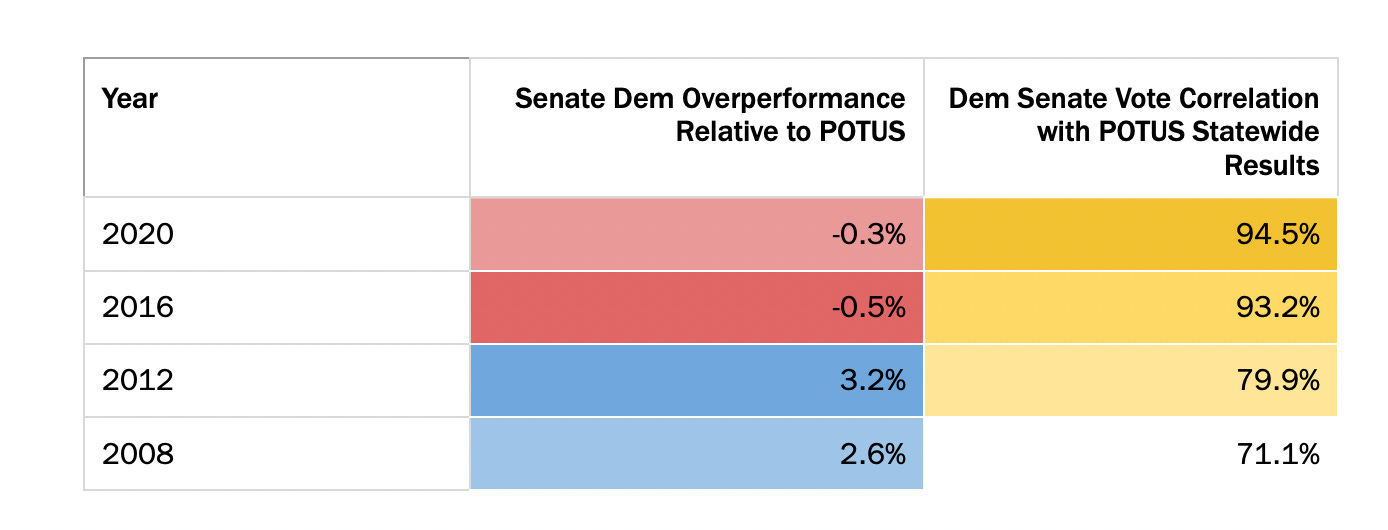

Both zero ticket-splitting and literally uniform national swings are simplifying assumptions; reality will be a bit more complicated. Incumbency advantage, in particular, might help stem the bleeding a little. But take a look at the table below, courtesy of David Shor, head of Data Science at Blue Rose Research (where I work). Both ticket-splitting and incumbency advantage have declined precipitously in recent years, and are both now near zero:

Overall, the combination of decreasing incumbency advantage and a poor national environment for Democrats means we should probably expect Democrats to control between 46 and 47 Senate seats after 2022 — depending, essentially, on whether or not Maggie Hassan manages to hold her seat in New Hampshire. And indeed, that’s what betting markets like PredictIt seem to think will happen.

The 2024 map is much worse

Since the Reagan Era, Democrats have averaged roughly 51% of the two-party vote in Presidential elections. If Biden gets this percentage of the vote, and the correlation between the Senate and presidential vote stays at close to .95 (as it was in 2020), then basically every Democratic senator in a state Biden won by less than 2% who is up in 2024 is likely to lose.

That includes:

Jon Tester in Montana (Biden -16.3)

Joe Manchin in West Virginia (Biden -29.9)

Sherrod Brown in Ohio (Biden -8)

Bob Casey in Pennsylvania (Biden +1.2)

Tammy Baldwin in Wisconsin (Biden +0.7)

Kyrsten Sinema in Arizona (Biden +0.3)

In addition, Debbie Stabenow in Michigan (Biden +2.8) and Jackie Rosen in Nevada (Biden +2.4) would likely be in toss-up races.

Putting it all together

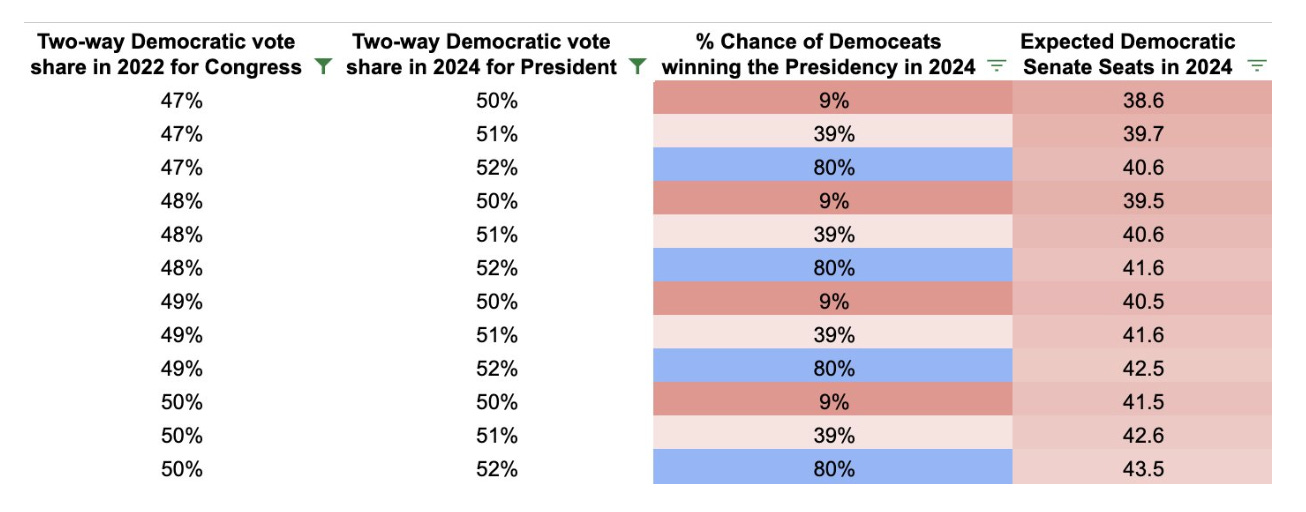

The above scenarios are designed to illustrate plausible outcomes, and they’re specific to certain assumptions about Democrats’ performance in the 2022 and 2024 elections. You might think these assumptions are wrong. So below is a “choose your own adventure” for Senate forecasts. Start on the left with the share of the vote you think Democrats will get in 2022, then pick your estimate of the Democratic vote share in 2024. The output in the right-most column is, according to David Shor’s modeling, the projected number of Senate seats Democrats will hold after the 2024 elections.

As the table demonstrates, “normal” electoral results will likely result in the loss of a large share of the Democratic Senate Caucus — pessimism about the outlook here is not driven by any particular pessimism about Democrats’ share of the national popular vote.

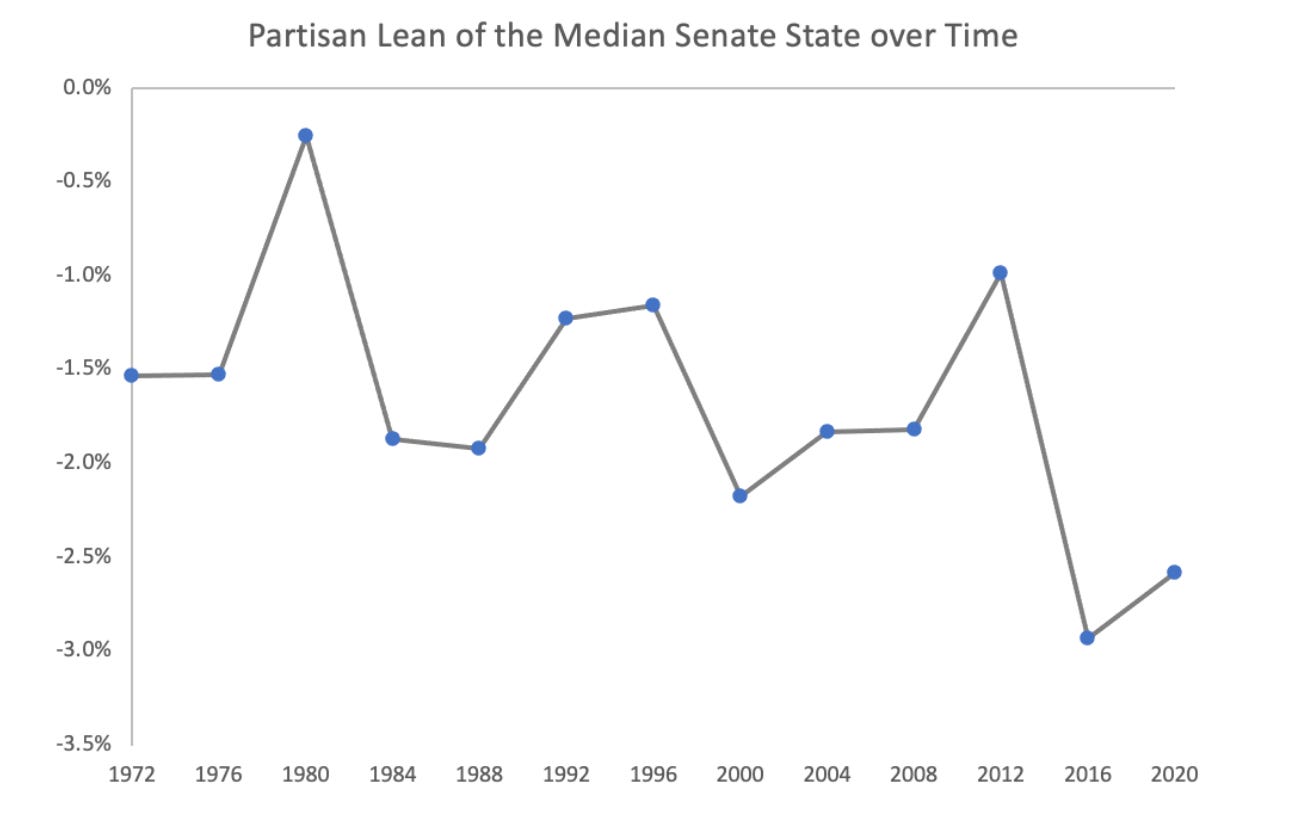

Instead, the issue is that the growing polarization of the electorate around educational attainment and the urban/rural divide has generated a Senate that is incredibly biased against the Democratic party.

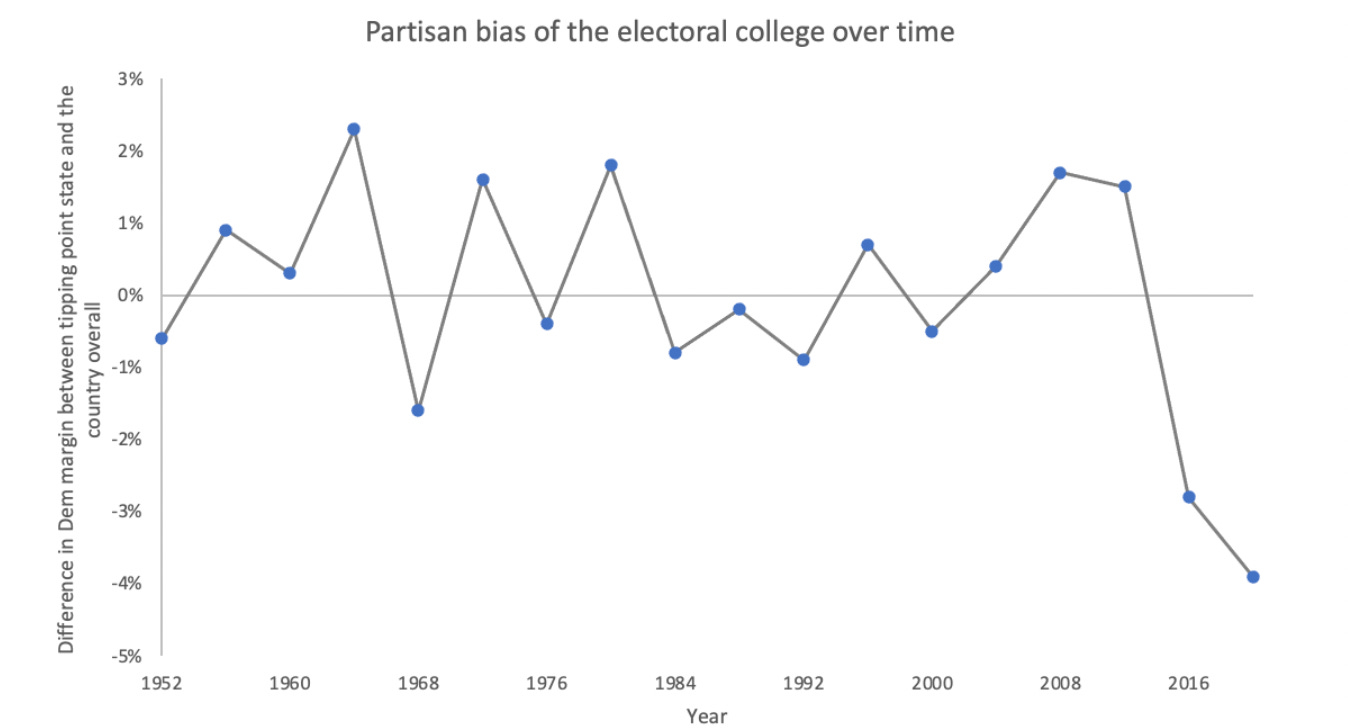

Meanwhile, the Electoral College is more biased than ever:

If Joe Biden receives 51% of the vote in 2024 (again, this is the long-run average for Democratic presidential candidates), he will likely lose the Electoral College — and with it, the presidency.

“Business as usual” will result in President Trump or President DeSantis, with somewhere between 56 and 62 Senate seats. And this is actually worse than it might seem at first. In recent years, Republican senators who have retired (or announced that they are retiring) have skewed heavily toward those who were willing to occasionally stand up to Trump, like Jeff Flake, Lamar Alexander, Rob Portman, Pat Toomey, and Richard Burr. If Trump returns to office, he will do so with a median Senator who is far more deferent to his wishes than the last time around.

Hope is not a plan

Of course, these dire predictions may not come to pass. Maybe Democrats will get 50% of the vote in 2022 (though this is looking more and more like a lost cause), and maybe they’ll follow that up with 54% of the vote in 2024. Then Biden will stay President, and Republicans will only have a slim Senate majority in 2024 — 53 seats instead of 58 or so.

This “optimistic” scenario is possible; Presidents have won re-election by more than 8% before. The bias of the maps is also not a law of nature. While it didn’t impact election outcomes, 2004, 2008, and 2012 all featured a modest Electoral College bias in favor of the Democratic Party coalition, offset by a modest Senate bias in favor of the GOP. In theory, Biden could shift back to Obama’s less-educated, more-rural pattern of support, reducing the Democratic party’s electoral disadvantage.

But it’s important to stress that this is not the business as usual case. The way-too-early 2024 polling has Biden and Trump tied in a hypothetical rematch. Betting markets have Republicans favored to retake the presidency. Democrats drawing even with Republicans in the popular vote in 2022 would be surprising, as would Biden winning reelection by more in 2024 than he did in 2020. A large realignment of demographic voting patterns, with rural and working-class voters returning to the Democratic party, seems even more improbable given the party’s current trajectory.

And neither an 8% landslide in 2024 nor a reshaping of electoral coalitions will happen by chance. The administration and the reelection campaign would have to make different tactical choices than the ones they’ve been making.

What tactical choices should they make? That’s a hard question, and it’s one I’ll be writing a lot more about in the months to come. But before you can solve a problem, you have to acknowledge that you have one. Aiming for 51-52% of the vote under the current coalitional pattern won’t cut it. Democrats need to wake up, because right now they’re sleepwalking into disaster, with no plan to avert it.