CONTEXT

I hope this isn't TL/DR.

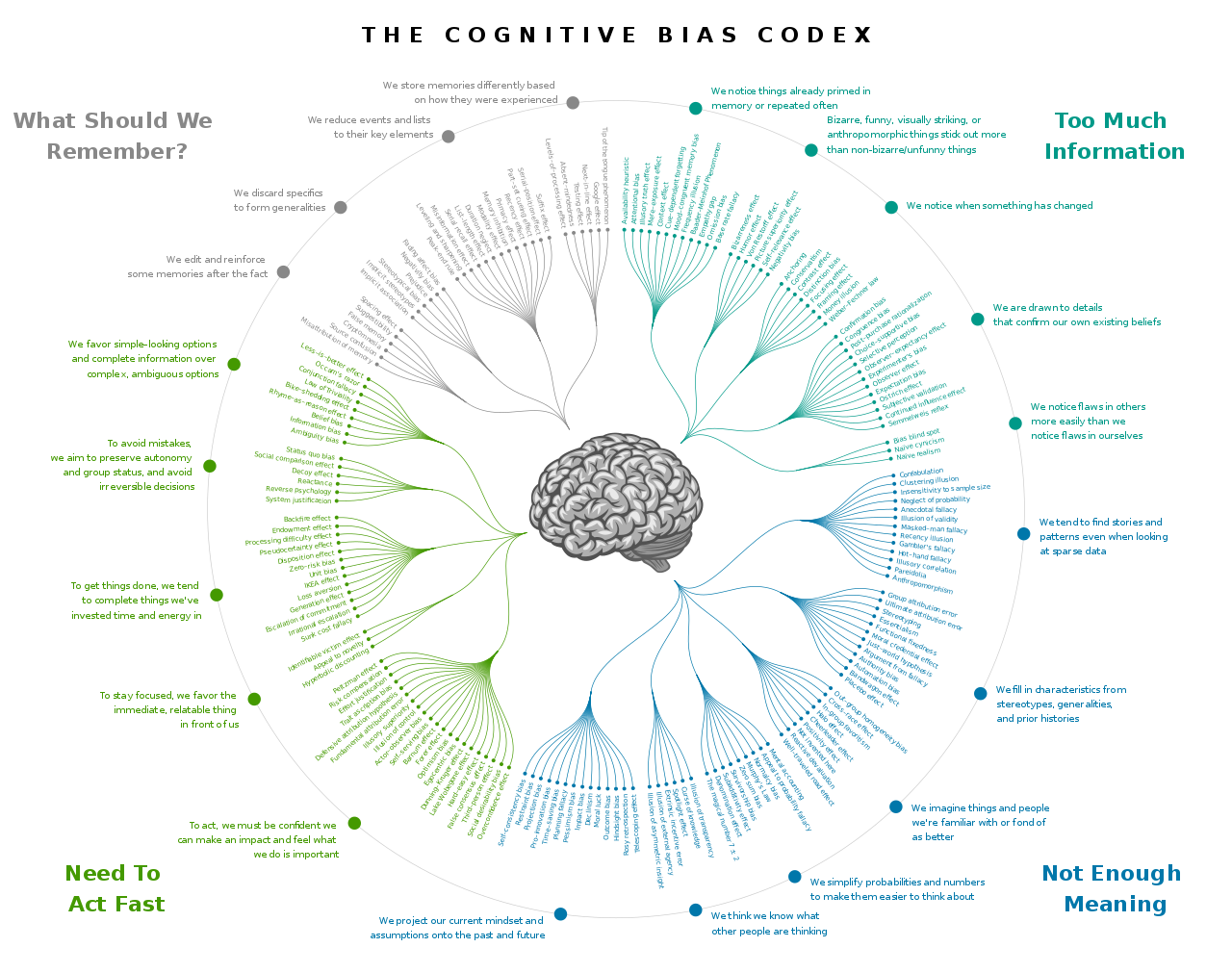

As we all know, humans are bundles of biases that usually operate mostly or completely unconsciously. At present there are 188 asserted biases that have been described, although some of them are species of, or overlapping with, broader biases. The narrower species biases are triggered by different kinds of inputs and/or social situations.

Biases are not all bad. Many tend to be tradeoffs between evolutionary forces (presumably pro-survival) and accurate perceptions of reality. Humans tend to overestimate risk because avoiding risk has an adaptive benefit, e.g., not being eaten by a predator. Some biases are adaptive, but some may be epiphenomena, or a side effect of an adaptation bias.

THE SERIAL DEPENDENCE BIAS (SDB)

SDB is used as an example of how researchers try to understand the source of biases by designing experiments that distinguish the kind of mental processing a bias arises from. SDB affects tends to bias a person’s current perception to be closer to what was perceived immediately before. In other words, what we perceive in the present is sometimes influenced by what we recently perceived. The first perception can prime us and influence the next. SDB has been observed using different stimuli, such as perception of tilt, number and motion. Thus, a big number or amount being seen first then another being seen, tends to lead the observer to thing the new number or amount is bigger than an unbiased perception.

What was not known about SDB was whether biasing occurred during sensory perception (a sensory (visual) processing bias) or cognition (biased thinking about what was seen). To untangle visual bias from cognitive bias, researchers in Japan asked subjects to estimate the number of coins they just saw for 0.5 second on a computer screen (visual processing bias) and their total monetary value (cognitive bias).

If the previous number of coins just viewed was dominant that would bias subsequent reported perceptions then that would be evidence that SDB is primarily a perceptual bias. But, if the prior value estimate affected later estimates, that would be evidence that SDB is primarily a higher cognitive phenomenon. In that case, a prior high value estimate would tend to make a subsequent value estimate higher. In other words, the earlier estimate would have a greater effect than the value actually present.

The data indicates that SDB is mostly a higher cognitive function (estimated value of coins), not a bias in visual processing (number of coins seen). See the places where the bias can arise, vision alone, cognitive value estimation alone, or a combination of both?

EurekAlert! described the experiment like this:

Experiments were conducted in which between 8 to 32 Japanese coins of three types—silver one yen, gold five yen, and copper ten yen—were displayed on screen for half a second. In the first experiment, the 24 participants guessed the total number of coins that appeared on the screen 250 times; in the second experiment, participants saw coins appear on the screen, but guessed the total value of the money displayed 250 times. Serial dependence was confirmed for both tasks: it was found that a participant’s last guess, not the coins that they had just seen for half a second, had the greatest effect on how they answered. These results indicate that higher-order cognitive processing has a greater influence on the occurrence of serial dependence.

Participants were asked to estimate the total number of coins presented on the screen. The stimulus duration was 500 ms [0.5 second], and the number of coins ranged from 8 to 32. This made it impossible for participants to accurately count the number of coins. Participants thus answered by estimating the number of coins [and by estimating their total value].

SDB has some serious real world effects. Steven Novella at Neurologica blog writes:

Understanding serial dependence bias has real world implications. One study, for example showed that radiologists display serial dependence bias when reading radiographs. The researchers added simulated lesions to real radiographs. This allowed them to control for the properties of the lesions – are they light or dark, for example. They found that serial dependence bias pulled the radiologists in the direction of finding similar lesions by 13%. This is a large effect size in this context. Finding a dark lesion on a film primed the radiologists to better detect similar dark lesions on subsequent films.

Serial dependence bias can also be either attractive or repulsive – it can pull later perception toward the previous stimuli or push it away. In one study, for example, they looked at estimates of direction heading and found a repulsive serial dependence bias. This seems to favor change rather than consistency. This implies that serial dependence bias is context dependent, which makes sense if it is a higher cognitive phenomenon.

We can potentially compensate for this bias if we are aware of it. Knowing that once you are primed to see a thing you will begin to see it everywhere can help us make sense of the world, and avoid spurious conclusions.

And this exemplifies why (i) it is useful to know something about human biases, and (ii) the ways that researchers can look at subtle differences in mental processing, in this case visual vs cognitive.

WHAT ABOUT POLITICS?

Is SDB relevant to politics? Maybe. This is the abstract of a 2016 research paper:

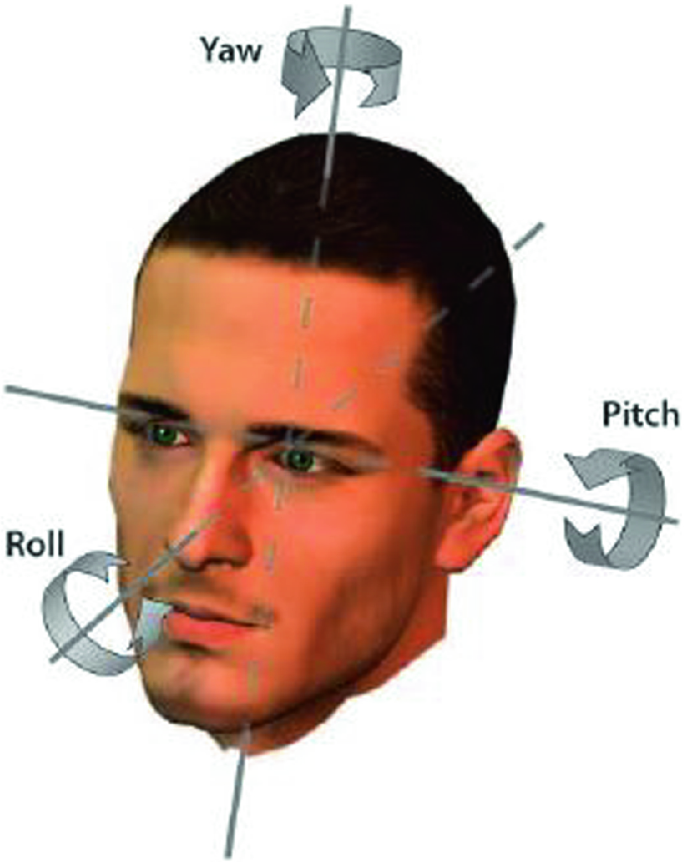

Once a face is detected, its retinal image will be continually distorted by changes in eye position, noise, lighting and many other factors. Yet from one moment to the next our perception of a face is stable. Recent advances have indicated there is a mechanism for achieving the continuous perception of a person’s identity that pools across prior and present visual inputs. There is still debate as to whether the perception of face attractiveness is also serially dependent. Here we investigate continuity in the perception of attractiveness using a one back [t−1] effect as a marker of serial dependence. Our results show that face attractiveness is biased towards the attractiveness of the previous face, and that this effect is robust despite changes in viewpoint involving rotations around the yaw axis [turning head left or right]. However, face attractiveness perception is released from this form of rapid adaption when the previously seen face differed in orientation due to a rotation around the roll axis [tilting head left or right].

How to translate that into politics? Maybe like this: Before a male (or female) candidate appears on TV:

1. Have an attractive or good looking man (or woman) appear first as a mental primer to least briefly to say something;

2. Make sure that the primer decoy does not tilt their head left or right, i.e., no roll axis movement; and

3.Then show the candidate and make sure he/she does not not tilt their head left or right because tilting the head left or right breaks the positive bias link to the primer decoy the candidate wants to stay cognitively linked to.

Is that a trivial thing? I don’t know. There is plenty of evidence in social science literature that says that a candidate’s attractiveness is a factor in people liking or disliking them, especially when differences between candidates are perceived to be small. A 2011 research paper commented:

This study examines the cognitive and affective factors of candidate appraisal by manipulating candidate attractiveness and levels of issue agreement with voters. Drawing upon research in evolutionary psychology and cognitive neuroscience, this analysis proposes that automatic processing of physical appearance predisposes affective disposition toward more attractive candidates, thereby influencing cognitive processing of issue information. An experimental design presented attractive and unattractive candidates who were either liberal or conservative in a mock primary election. The data show strong partial effects for appearance on vote intention, an interaction between appearance and issue agreement, and a tendency for voters to assimilate the dissimilar views of attractive candidates. We argue that physical appearance is important in primary elections when the differences in issue positions and ideology between candidates is small.

If a professional advisor was advising a candidate, they might tell a candidate to start with someone who makes them look better (primer decoy), and then try to make their political positions look different and non-threatening but also similar to those of popular politicians. It's a tricky thing, but it's probably something that professionals and candidates are aware of and would like to exploit when reasonably possible.

See all the ways that a person can try to influence what people think they see and how they react to it? For morally bankrupt politicians, the ways to effectively deceive are numerous and subtle. The temptation to deceive is probably almost always too great for the morally rotted to ignore.

No comments:

Post a Comment