This is for a reference at another site I am engaged with.

Pragmatic politics focused on the public interest for those uncomfortable with America's two-party system and its way of doing politics. Considering the interface of politics with psychology, cognitive biology, social behavior, morality and history.

Etiquette

Wednesday, November 22, 2023

News bits: Fascism?; Mandatory defense against the dark arts education!; DJT's open attack on justice

Trump’s Dire Words Raise New Fears About His Authoritarian Bent

The former president is focusing his most vicious attacks on domestic political opponents, setting off fresh worries among autocracy expertsDonald J. Trump rose to power with political campaigns that largely attacked external targets, including immigration from predominantly Muslim countries and from south of the United States-Mexico border.But now, in his third presidential bid, some of his most vicious and debasing attacks have been leveled at domestic opponents.

During a Veterans Day speech, Mr. Trump used language that echoed authoritarian leaders who rose to power in Germany and Italy in the 1930s, degrading his political adversaries as “vermin” who needed to be “rooted out.”

“The threat from outside forces,” Mr. Trump said, “is far less sinister, dangerous and grave than the threat from within.”

Pushing back against the surge of misinformation online, California will now require all K-12 students to learn media literacy skills — such as recognizing fake news and thinking critically about what they encounter on the internet.

Gov. Gavin Newsom last month signed Assembly Bill 873, which requires the state to add media literacy to curriculum frameworks for English language arts, science, math and history-social studies, rolling out gradually beginning next year. Instead of a stand-alone class, the topic will be woven into existing classes and lessons throughout the school year.

“I’ve seen the impact that misinformation has had in the real world — how it affects the way people vote, whether they accept the outcomes of elections, try to overthrow our democracy,” said the bill’s sponsor, Assemblymember Marc Berman, a Democrat from Menlo Park. “This is about making sure our young people have the skills they need to navigate this landscape.”

The new law comes amid rising public distrust in the media, especially among young people. A 2022 Pew Research Center survey found that adults under age 30 are nearly as likely to believe information on social media as they are from national news outlets. Overall, only 7% of adults have “a great deal” of trust in the media, according to a Gallup poll conducted last year.

“The increase in Holocaust denial, climate change denial, conspiracy theories getting a foothold, and now AI … all this shows how important media literacy is for our democracy right now,” said Jennifer Ormsby, library services manager for the Los Angeles County Office of Education. “The 2016 election was a real eye-opener for everyone on the potential harms and dangers of fake news.”

“Media literacy is a basic part of being literate. If we’re just teaching kids how to read, and not think critically about what they’re reading, we’re doing them a disservice.”

AB 873 passed nearly unanimously in the Legislature, underscoring the nonpartisan nature of the topic.

Nationwide, Texas, New Jersey and Delaware have also passed strong media literacy laws, and more than a dozen other states are moving in that direction, according to Media Literacy Now, a nonprofit research organization that advocates for media literacy in K-12 schools.

Still, California’s law falls short of Media Literacy Now’s recommendations. California’s approach doesn’t include funding to train teachers, an advisory committee, input from librarians, surveys or a way to monitor the law’s effectiveness.

A panel of three judges on Monday appeared highly skeptical of arguments from Donald Trump's legal team seeking to revoke a gag order that bars him from attacking potential witnesses in his election interference criminal case.

D. John Sauer, Trump's attorney in the hearing before the United States Court of Appeals for the DC Circuit, took a highly expansive view of the former president's First Amendment rights.

Depending on "the context," Sauer argued, Trump would be permitted to pressure possible witnesses not to cooperate with prosecutors.

Judge Patricia Millet, an Obama appointee on the panel, repeatedly pressed Sauer to explain if Trump could ever be restricted from saying anything. She appeared annoyed when he avoided articulating any such standard.

"So is it your position that if he communicates through a social media post: 'Hey, Witness X, I know the prosecutor is bothering you, trying to get you to say bad things about me — be a patriot, don't act treasonously, don't cooperate'—" she began to ask Sauer.

Sauer interrupted the judge, saying it would "depend on the context" if it would be OK for Trump to pressure a witness in a public setting, and declined to answer the question directly.

After several minutes of back-and-forth with the judge — What if it was a "fair response" to something Witness X said? What if it was in the "political arena"? What if it was about former Vice President Mike Pence, who until recently challenged Trump for the 2024 Republican presidential nomination? — Sauer finally conceded that there were possible circumstances where Trump would be violating the order.

Trump's attorneys have sought to get rid of the gag order entirely, arguing that it infringes on his First Amendment rights, which they say is particularly heightened since he is the frontrunner for the Republican nomination in the 2024 presidential election. Chutkan scheduled a trial for March.

"What they've described as 'threats' is actually, under the Supreme Court's jurisprudence, pure political speech," Sauer said. "It is rough and tumble, it is hard-hitting in many situations, but it absolutely is core political speech."

How does the public view election deniers?

https://publicwise.org/publication/how-does-the-public-view-election-deniers/

Key Takeaways

- A strong majority of self-identified moderate, liberal and progressive registered voters say they are less likely to vote for an election denier.

- Conversely, conservative voters say they are more likely than not to vote for a candidate labeled an election denier.

- The overwhelming majority of Americans have heard common election denier claims about voting and elections.

- Despite this prevalence, there is no clear consensus on what election denier means to the average registered voter. That did not stop the majority from saying they are less likely to vote for one.

- Because the election denier label has not gained a solid, agreed upon definition, there is an opportunity for defenders of democracy to shape and broaden the narrative.

- Up to 14% of progressive voters believe some election denier claims, suggesting pro-democracy candidates would benefit from efforts to guard against susceptibility to conspiracy claims even among progressive and liberal base voters.

The persistence of election denialism and election denying candidates

During the 2020 election cycle, then President Donald Trump began to cast doubt on the outcome of the election before voting had even begun. Following Joe Biden’s election, Trump and his supporters continued to cast doubt on the results, despite evidence that the 2020 election was the most secure in recent history. This burgeoning election denialism movement culminated in the violent insurrection at the Capitol on January 6, 2021, resulting in five deaths, nearly 1,000 arrests, and the largest investigation in U.S. history.

In the 2022 midterms, a swath of candidates up and down the ballot embraced election denialism as a rallying campaign cry premised on the “Big Lie” of election fraud. Although most election denying candidates did not win their elections for state-wide positions, a majority overall won their races, including to the U.S. House and to many state legislatures and local offices around the country.

These wins demonstrate the extent to which election denialism has found a foothold in American politics, both among elected representatives and the voting public. We should expect the election denying platform will continue to persist into the coming 2024 Presidential election.

But will Americans vote for election deniers? And what does calling someone an “election denier” candidate mean to the general public?

At Public Wise, we wanted to know more about how Americans understand election deniers and election denialism more broadly. Specifically, what characteristics do they believe most accurately describe an election denier? What election denial rhetoric have voters heard and to what extent do they believe it is true? And, can voters be persuaded to vote for a candidate widely portrayed as an election denier?

In this analysis, we draw from our nationally representative survey of registered voters conducted from April 13-19th, 2023. We asked questions related to views of election deniers and election denial rhetoric, beliefs about democracy, threats to democracy, and opinions about current political issues.1

In this first installment of our new Democracy and Election Deniers series, we delve into whether Americans are willing to vote for an “election denier,” to what extent they are familiar with election denial talking points, and what they think “election denier” refers to.

Willingness to vote for election denying candidates

Are people willing to vote for a candidate who has been characterized as an election denier?

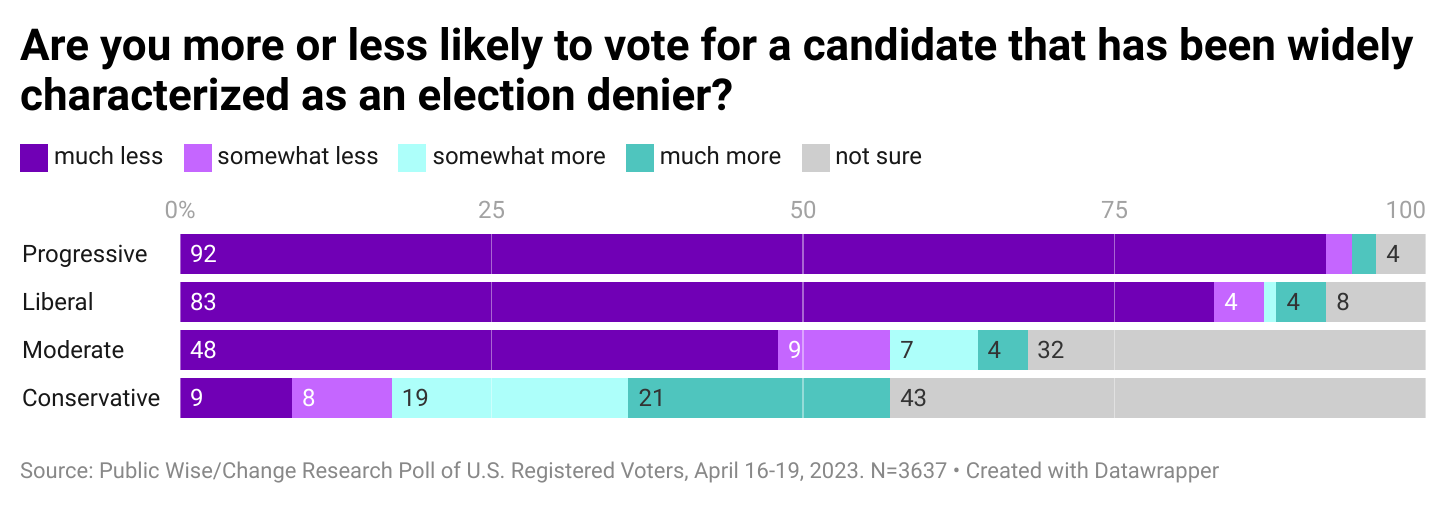

The answer seems to depend on ideology. Progressives and liberals overwhelmingly report that they are less likely to vote for an election denier. The majority of moderates, at 57%, also say they are less likely to vote for a candidate who has been characterized as an election denier. Meanwhile, only 17% of conservatives say they are less likely and a full 40% report conversely that they are more likely (19% somewhat more and 21% much more) to vote for such a candidate.

While there is a lot of certainty on the left side of the political spectrum, there is less so in the middle and on the right. Almost a third of moderates and more than 40% of conservatives report that they are not sure if they would vote for a candidate who has been widely characterized as an election denier. This suggests that the election denier label will have different strategic uses for candidates and their campaigns depending on the voters they are trying to sway.

How conspicuous are election denier claims and who believes them?

The majority of registered voters said that they are less likely to vote for a candidate who has been widely characterized as an election denier in general. But how prevalent are election denier claims and what kinds of voters believe them?

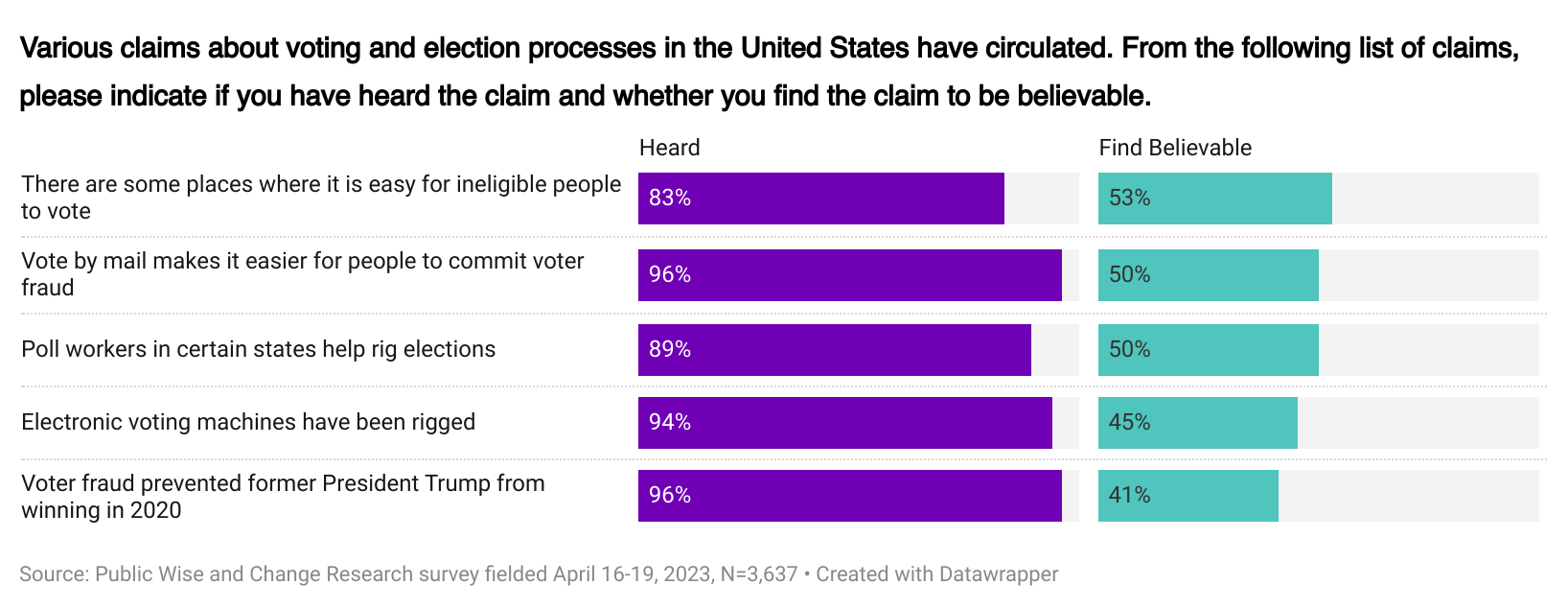

We asked about five common election denier claims. We found exposure to election denial rhetoric is widespread, but belief in election denial rhetoric is split along ideological lines.2

Virtually all registered voters report having heard election denier rhetoric of some kind, but some claims appear to be more believable than others. Slightly over half (53%) of all respondents found it believable that there are places where it is easy for ineligible people to cast ballots, and 50% of all respondents found it believable that vote by mail makes it easier for people to commit fraud and that poll workers in certain states help rig elections.

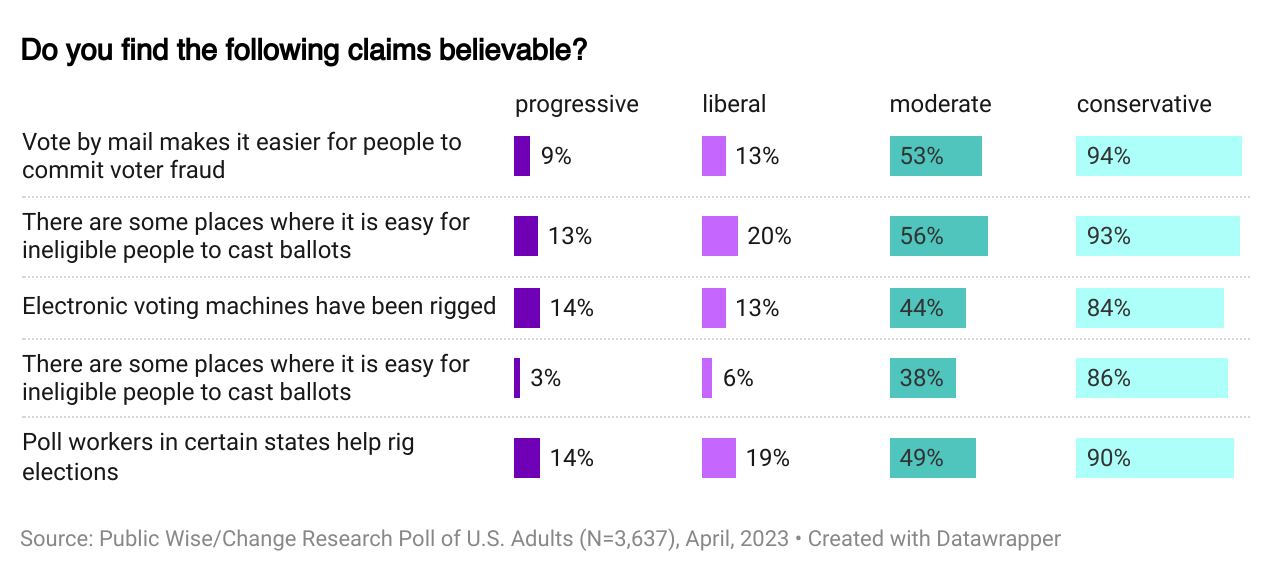

Most conservatives find all election denier claims believable. Moderates are more likely to believe each claim compared to progressives, but less likely to believe them compared to conservatives.

A small but substantial share of liberals and progressives found some election denier claims to be believable. 13% of progressives and 20% of liberals find the claim that there are some places where it is easy for ineligible people to cast ballots to be believable.

Another 14% of progressives and 19% of liberals find it believable that poll workers in certain states help rig elections.

What are the defining characteristics of election deniers?

Registered voters have largely heard election denial rhetoric and the majority report they are less likely to vote for a candidate who has been characterized as an election denier, but do they have a common understanding of what it means to be an election denier? It seems like the answer is no. This may reflect a combination of factors, including the fact that across plenty of media coverage referring to election deniers the term is being used to describe many different behaviors with very little overlap across sources and that election deniers themselves have engaged in many combinations of these behaviors.

In their definition of election deniers, The Washington Post includes people who questioned Biden’s victory (e.g. Belief in the Big Lie of election fraud), opposed counting electoral votes, and sought to overturn the 2020 election.

Many of these characteristics correspond to a variety of other anti-democratic views, but the full range of beliefs and behaviors the public associates with those labeled as election deniers remains unclear.

For example, election deniers have been broadly characterized as believing in and spreading conspiracy theories and false claims about voter fraud. But they also cast doubt on legitimate voting options such as vote by mail, claiming – without evidence – it is a mechanism for widespread voter fraud. These claims about voter fraud are then used to justify support for voter suppression legislation.

In fact, the Brennan Center for Justice released a “playbook” of election denier candidates, pointing to a number of strategies they tend to employ, including spreading misinformation, efforts to suppress votes, threatening poll workers, discrediting voting machines, and undermining vote-by-mail.

Given the scope of election denier characteristics, their tendency to support voter suppression, and the conspicuousness of their claims in the wider media landscape, we wanted to know whether any of these other descriptions – above and beyond denying the 2020 election results – are salient for voters as accurate portrayals of election denier candidates.

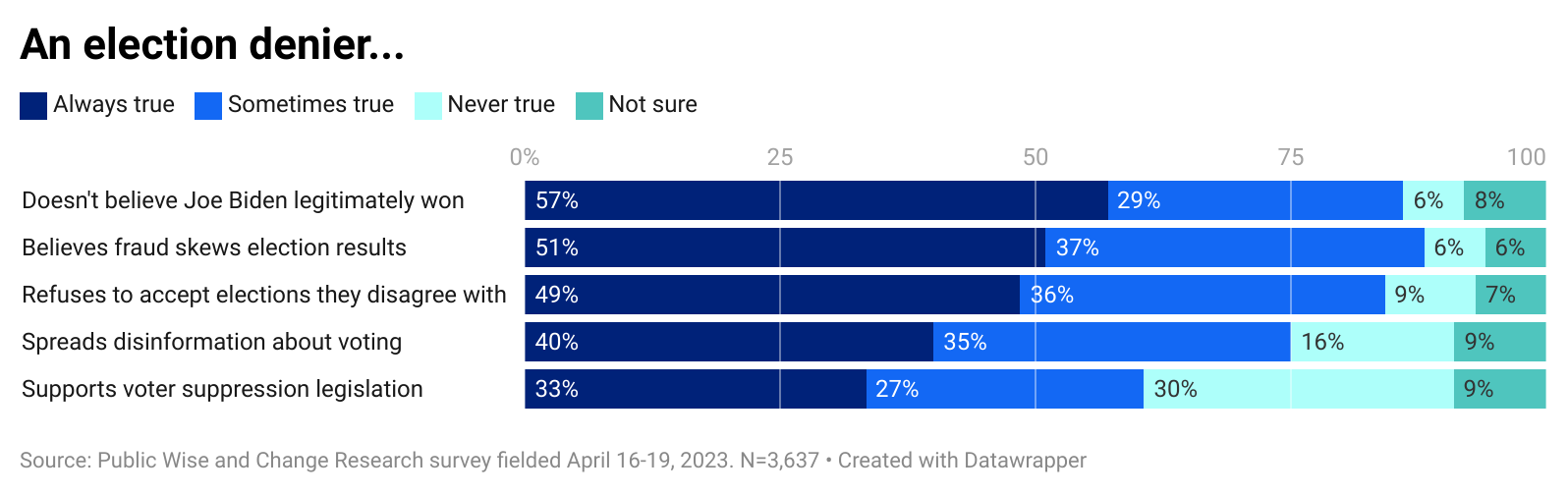

In our survey, we asked participants to assess whether the following five statements about someone labeled an election denier are always true, sometimes true, never true, or not sure:

- An election denier does not believe Joe Biden legitimately won the 2020 election

- An election denier supports legislation that makes it harder for eligible American citizens to vote

- An election denier refuses to accept the results of elections they disagree with

- An election denier spreads disinformation regarding voting and elections

- An election denier believes voter fraud occurs frequently enough to skew election results

Slightly more than half of registered voters claim two characteristics are “always true” of election deniers: that they do not believe Joe Biden legitimately won the 2020 election (57%) and they believe voter fraud happens frequently enough to skew election results (51%).

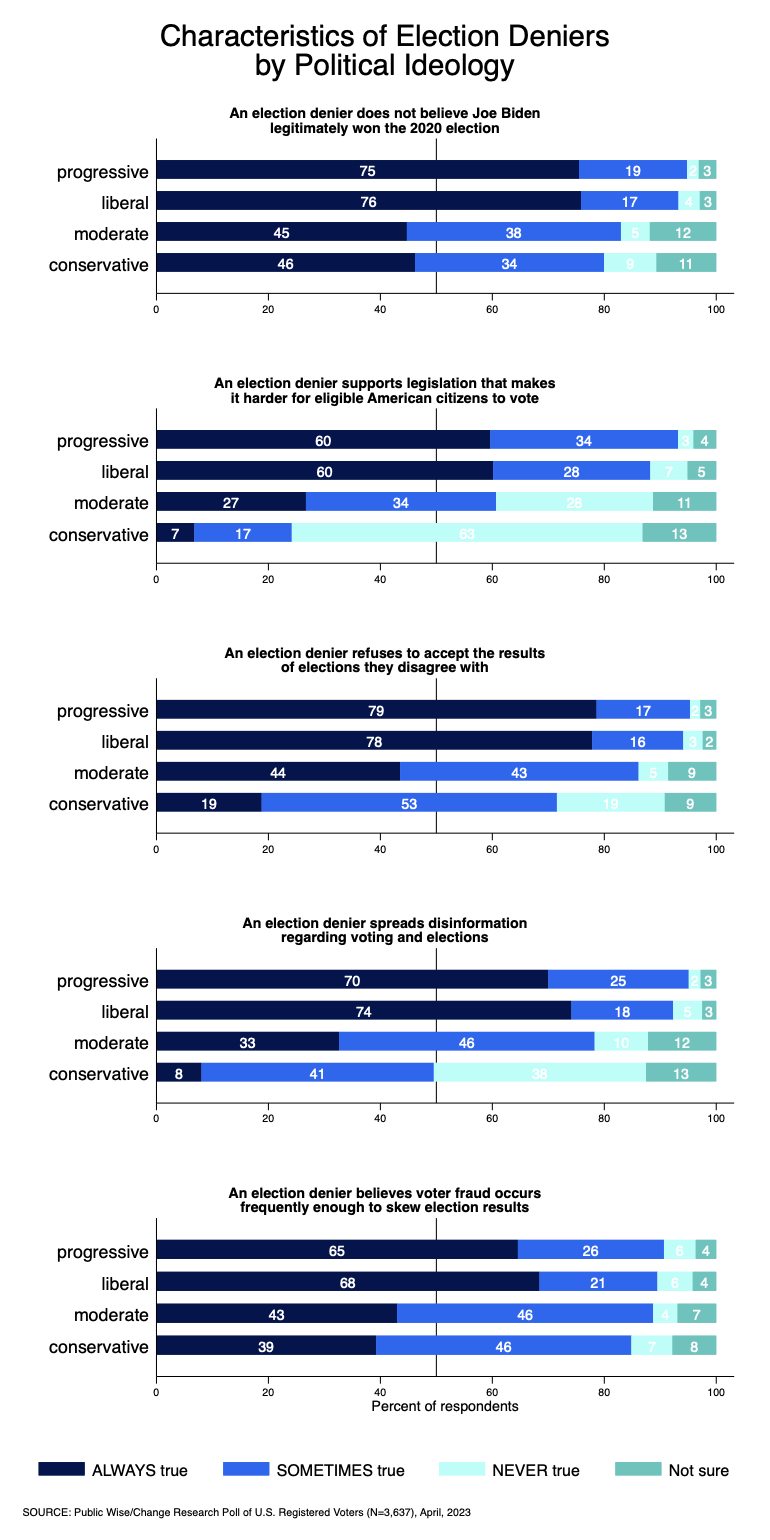

The extent to which respondents felt each of the five descriptors applied to election deniers varied widely by partisan ideology.3 Between 60-78% of liberals and progressives responded “always true” for all items, while roughly half or less of all conservative respondents said “always true” for all items. Similar to views on accountability for January 6th, these wide ideological splits are obscured by the overall average.

Despite being a common campaign message of election denier candidates, only 65% of progressives and 68% of liberals said it is “always true” that election deniers believe voter fraud occurs frequently enough to skew election results, compared to 43% of moderates and 39% of conservatives.

The description garnering the largest share of progressives and liberals claiming it is “always true” is that election deniers refuse to accept the results of elections they disagree with. On the other hand, there was no one election denier description that was “always true” for the majority of conservatives. The statement that election deniers do not believe Biden legitimately won in 2020 came closest with 46% of conservatives saying it is always true.

There is also ideological disagreement about the extent to which election deniers support voter suppression legislation: 60% of both liberals and progressives said it is “always true” that election deniers support legislation that make it harder for eligible citizens to vote, while 63% of conservatives said this is “never true” of election deniers. 27% of moderates thought this is always true of election deniers, while another 28% thought it is never true.

These results show that while most registered voters have heard some form of election denial rhetoric, there is not one clear definition of election denier that resonates with the American public, and the characteristics that ring most true differ across ideological lines. Despite this lack of clear definition, the majority of registered voters still said they were less likely to vote for an election denier.

Looking ahead: clearly communicate the election denier agenda and how it harms democracy

Although election denialism was a decisive issue of the 2022 midterms, our findings suggest that registered voters do not have a consistent picture of what an election denier looks like. In our survey, barely more than half (57%) said that it is always true that an election denier is someone who does not believe that Biden legitimately won the 2020 election, despite many news organizations widely agreeing on that as a condition for labeling someone an election denier.4

While the 2022 elections are over, the broader election denial movement is not. At the top of the ticket, Trump has already entered the 2024 race with early polling suggesting he leads other candidates by a wide margin. And he’s not the only election denier running for office. Many election deniers currently in office will be running for reelection and many others will try to take new positions, including those that directly oversee election administration.

Moreover, in the nearly three years since the 2020 election and insurrection that followed, the election denial movement and its implications have grown far beyond the lie that Trump won the 2020 election. Much of the rhetoric used to push this lie relied on false claims about the security of US elections, including lies about voter fraud, vote by mail, poll workers, electronic voting machines, and ballot counting procedures. The post-2020 election denier playbook builds on these lies with an agenda designed to limit voting by mail, complicate the counting of votes with things like hand count requirements and audits, and change who controls the certification of results. These lies have also been used to justify voter suppression legislation, even in states like Georgia where Republican officials defied Trump’s demands to find him the votes he needed to win the 2020 election.

As we move closer to 2024, the urgency of communicating these goals – and the harm that comes with them – continues to grow. Our data suggest that, in addition to many not thinking it is always true that election deniers reject Biden’s legitimate win in 2020, many Americans also remain unaware of other key features of election denialism. Only about half said it is always true that election deniers believe fraud skews election results (51%) and that election deniers refuse to accept the results of elections they disagree with (49%). Only 40% said it’s always true that election deniers spread disinformation about voting, and even fewer, 33%, said it’s always true that election deniers support voter suppression legislation.

The upside for democracy is that election deniers and the key claims of their movement remain unpopular among many Americans. While their rhetoric is widespread in the sense that almost everyone has heard their lies about elections and voting, belief in these lies is not widespread, especially among Democrats, left-leaning Independents, and a sizable share of moderates. Many also say they are much less likely to vote for someone who has been widely characterized as an election denier, including 92% of progressives, 83% of liberals, and 48% of moderates.

However, because many Americans remain unfamiliar with the key provisions of the election denier platform, there is an opportunity for defenders of democracy to broaden the narrative beyond denial of the 2020 election to encompass the bigger story of how these election denial behaviors fit into a broad threat to our democratic systems, particularly by explicitly connecting the lies about elections and voting to the candidates that seek to be in positions of power, especially those directly overseeing election administration.

Tuesday, November 21, 2023

Reasoning about the morality of lying and deceit in democracy

“[Johnson repeatedly told the American people] ‘the first responsibility, the only real issue in this campaign, the only thing you ought to be concerned about at all, is: Who can best keep the peace?’ The stratagem succeeded; the election was won; the war escalated. .... President Johnson thus denied the electorate of any chance to give or refuse consent to the escalation of the war in Vietnam. Believing they had voted for the candidate of peace, American citizens were, within months, deeply embroiled in one of the cruelest wars in their history. Deception of this kind strikes at the very essence of democratic government.”

She also rejects utilitarianism, which considers only the consequences of the lie regardless of extenuating circumstances. For utilitarians, a lie that confers more perceived benefit than harm is acceptable. Lies that harm no one are acceptable. The problem is that some harms and benefits cannot be accurately assessed. For example, lies that lead to social distrust and reduced social cohesion. Also, lies can harm the liar as noted above. Bok argues “the more complex the acts, the more difficult it becomes to produce convincing comparisons of their consequences.” She points out that when multiple people are involved, assessing benefit and harm are “well-nigh impossible.”

Insurrection decision: A short legal analysis

Trump, plaintiffs appeal Colorado 14th Amendment rulingFormer President Trump and the group of plaintiffs battling over whether the former president should be disqualified from the Colorado ballot under the 14th Amendment both appealed the case to the state’s top court Monday.

A Colorado judge ruled Friday that Trump had engaged in insurrection by inciting the Jan. 6, 2021, Capitol riot, but the judge tossed the lawsuit by finding the 14th Amendment doesn’t apply to the presidency.

Trump in his appeal to the Colorado Supreme Court said he agreed with the latter part of the ruling keeping him on the state’s ballot but is appealing on other issues.

Left-leaning group Citizens for Responsibility and Ethics in Washington (CREW), which filed the lawsuit on behalf of four Republicans and two independent Colorado voters, asked Colorado’s top court to rule that the amendment does indeed apply to the presidency.

Colorado District Judge Sarah Wallace said that language means the amendment can’t be used to prevent Trump from appearing on the ballot, regardless of whether the then-president’s actions on Jan. 6 cleared the threshold.

Wallace ruled the presidency was not an “office … under the United States,” because the amendment explicitly lists all federal elected positions, except for the presidency and vice presidency. Wallace further ruled Trump was not an “officer of the United States” in the first place, referencing other constitutional provisions that distinguish the presidency from federal officers.

News bits: New coup attempt video; A DJT warning (again, sigh); Best people flock to MAGA!!

Conspiracy theorists pointed to one clip they say proved federal agents were present at the riot. They have argued a video shows one rioter, Kevin Lyons, wearing one of Trump's signature "Make America Great Again" hats, while flashing an official government identification badge at a camera.Skeptics, however, pointed out that Lyons was actually holding a vape—not a government ID—pouring cold water on the theory. Several high-profile conservatives pushed the theory, but were forced to backtrack amid criticism.Sen. Mike Lee of Utah was among the Republicans who backed the theory, retweeting a post on X, formerly Twitter, Saturday night questioning whether Lyons was an "undercover federal agent."

"I can't wait to ask FBI Director Christopher Wray about this at our next oversight hearing. I predict that, as always, his answers will be 97% information-free," Lee wrote in a post on X.

Lee's post remained public Monday morning, and he has not addressed criticism that Lyons was actually holding a vape, despite a community note from X fact-checking him on the matter: "The person is not flashing a badge. He is not a government employee or source. It is Kevin Lyons, who was recently sentenced to 4 years in jail for his actions on January 6th. He called police officers Nazis,'" the community note reads.

“Our democracy hangs by a thread”: Expert panel says a Trump victory in 2024 will end itFight through the trauma and exhaustion, our panel urges: The 2024 election could “end the American experiment”Donald Trump and the movement he represents are not “just” a matter of politics: They are effectively a public health crisis that touches all areas of American society and life.

These assaults on democracy and a humane society are emotional, physical, spiritual, psychological, economic, intellectual and material. Trumpism and fascism attack reality and truth, seeking to replace them with what social psychologists have described as a state of “malignant normality."

The result of these assaults is a collective state of trauma, anxiety, lack of direction and growing despair about our futures as individuals and citizens of a supposed democracy. These negative emotions are amplified by existential fears about global climate disaster, disruptive technologies such as AI, wars in multiple areas of the world, past and future pandemics and other unpredictable crises.

Fascism and authoritarianism are like opportunistic predators. They seek out societies in crisis whose dysfunction and brokenness allow them to flourish.If Trump and his MAGA forces take back the White House, whether by fair means or foul — a once-unthinkable prospect that now seems increasingly likely — that might finally mean the end of innocence for those Americans who have deluded themselves into believing that “we are better than that.”Cheri Jacobus is a former media spokesperson at the Republican National Committee:I look at the poll numbers and realize that half the country supports a lying, treasonous, dangerous, racist, sexist authoritarian who is under indictment, has been found liable for massive fraud, and who may be elected president because he's good for Fox News ratings and does Vladimir Putin's bidding. He's a lifelong criminal who likely sold or otherwise provided classified and top secret intelligence to our enemies and adversaries, and who managed to install a federal judge in the right jurisdiction to delay and obstruct his case, and generally assist him in covering up his crimes.

Joe Walsh was a Republican congressman and a leading Tea Party conservative:

Our democracy hangs by a thread, and a Trump victory in 2024 will end our democracy as we know it. People right now don't see this, and I worry that all the noise and chaos going on all over the world will keep people from recognizing the looming threat right in front of us. Biden looks overwhelmed by it all. That only strengthens Trump. .... What scares me the most right now is what's always scared me the most: Trump back in the White House, and a radicalized former political party of mine taking a sledgehammer to our democracy and our Constitution. The only thing that gives me hope is young people. Not because they understand any of this, but because they have the potential to understand. Older Americans are set in their ways. They're gone. Young people need to save this thing. I don't know if they will. But I know they can.

Right-Wing ‘Moms for Liberty’ Organizer Isa Convicted Sex OffenderMOMS FOR LIBERTY is a conservative parental rights group that has chapters all over the United States working to eradicate LGBTQ-related discussion in public schools, at least partially under the belief that educators are using it to “groom” children for sexual relationships. The group might want to look inward first. The Philadelphia Inquirer reported on Monday that Phillip Fisher Jr. — a pastor, Republican ward leader, and faith coordinator for Moms for Liberty in Philadelphia — is a registered sex offender.

Fisher was convicted in 2012 for aggravated sexual abuse of a 14-year-old boy, with the charging documents saying that Fisher, then 25, engaged and oral and anal [😮] sex with the boy. Fisher, who pleaded guilty, told the Inquirer that the conviction was a “railroad job” by a PAC affiliated with Lyndon LaRouche, the cult-y former presidential candidate whose organization Fisher worked for at the time. “It was a political situation that happened between me and Lyndon LaRouche,” Fisher said. “It was a member of his camp, his party, that made the accusation. They pushed it through.”