https://publicwise.org/publication/how-does-the-public-view-election-deniers/

Key Takeaways

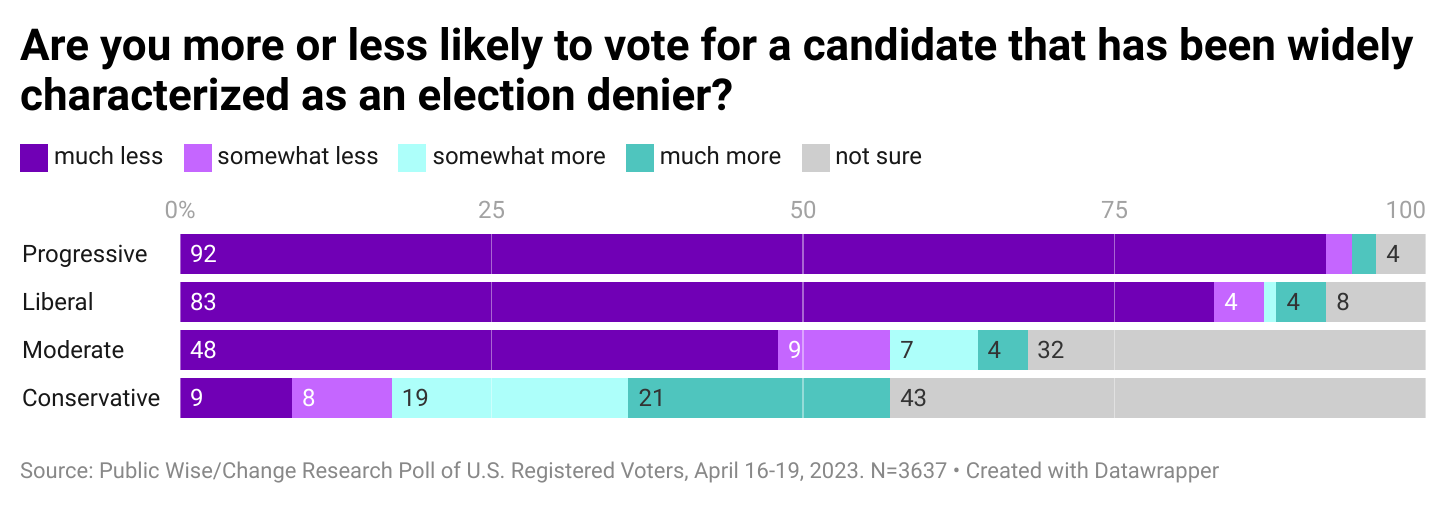

- A strong majority of self-identified moderate, liberal and progressive registered voters say they are less likely to vote for an election denier.

- Conversely, conservative voters say they are more likely than not to vote for a candidate labeled an election denier.

- The overwhelming majority of Americans have heard common election denier claims about voting and elections.

- Despite this prevalence, there is no clear consensus on what election denier means to the average registered voter. That did not stop the majority from saying they are less likely to vote for one.

- Because the election denier label has not gained a solid, agreed upon definition, there is an opportunity for defenders of democracy to shape and broaden the narrative.

- Up to 14% of progressive voters believe some election denier claims, suggesting pro-democracy candidates would benefit from efforts to guard against susceptibility to conspiracy claims even among progressive and liberal base voters.

The persistence of election denialism and election denying candidates

During the 2020 election cycle, then President Donald Trump began to cast doubt on the outcome of the election before voting had even begun. Following Joe Biden’s election, Trump and his supporters continued to cast doubt on the results, despite evidence that the 2020 election was the most secure in recent history. This burgeoning election denialism movement culminated in the violent insurrection at the Capitol on January 6, 2021, resulting in five deaths, nearly 1,000 arrests, and the largest investigation in U.S. history.

In the 2022 midterms, a swath of candidates up and down the ballot embraced election denialism as a rallying campaign cry premised on the “Big Lie” of election fraud. Although most election denying candidates did not win their elections for state-wide positions, a majority overall won their races, including to the U.S. House and to many state legislatures and local offices around the country.

These wins demonstrate the extent to which election denialism has found a foothold in American politics, both among elected representatives and the voting public. We should expect the election denying platform will continue to persist into the coming 2024 Presidential election.

But will Americans vote for election deniers? And what does calling someone an “election denier” candidate mean to the general public?

At Public Wise, we wanted to know more about how Americans understand election deniers and election denialism more broadly. Specifically, what characteristics do they believe most accurately describe an election denier? What election denial rhetoric have voters heard and to what extent do they believe it is true? And, can voters be persuaded to vote for a candidate widely portrayed as an election denier?

In this analysis, we draw from our nationally representative survey of registered voters conducted from April 13-19th, 2023. We asked questions related to views of election deniers and election denial rhetoric, beliefs about democracy, threats to democracy, and opinions about current political issues.1

In this first installment of our new Democracy and Election Deniers series, we delve into whether Americans are willing to vote for an “election denier,” to what extent they are familiar with election denial talking points, and what they think “election denier” refers to.

Willingness to vote for election denying candidates

Are people willing to vote for a candidate who has been characterized as an election denier?

The answer seems to depend on ideology. Progressives and liberals overwhelmingly report that they are less likely to vote for an election denier. The majority of moderates, at 57%, also say they are less likely to vote for a candidate who has been characterized as an election denier. Meanwhile, only 17% of conservatives say they are less likely and a full 40% report conversely that they are more likely (19% somewhat more and 21% much more) to vote for such a candidate.

While there is a lot of certainty on the left side of the political spectrum, there is less so in the middle and on the right. Almost a third of moderates and more than 40% of conservatives report that they are not sure if they would vote for a candidate who has been widely characterized as an election denier. This suggests that the election denier label will have different strategic uses for candidates and their campaigns depending on the voters they are trying to sway.

How conspicuous are election denier claims and who believes them?

The majority of registered voters said that they are less likely to vote for a candidate who has been widely characterized as an election denier in general. But how prevalent are election denier claims and what kinds of voters believe them?

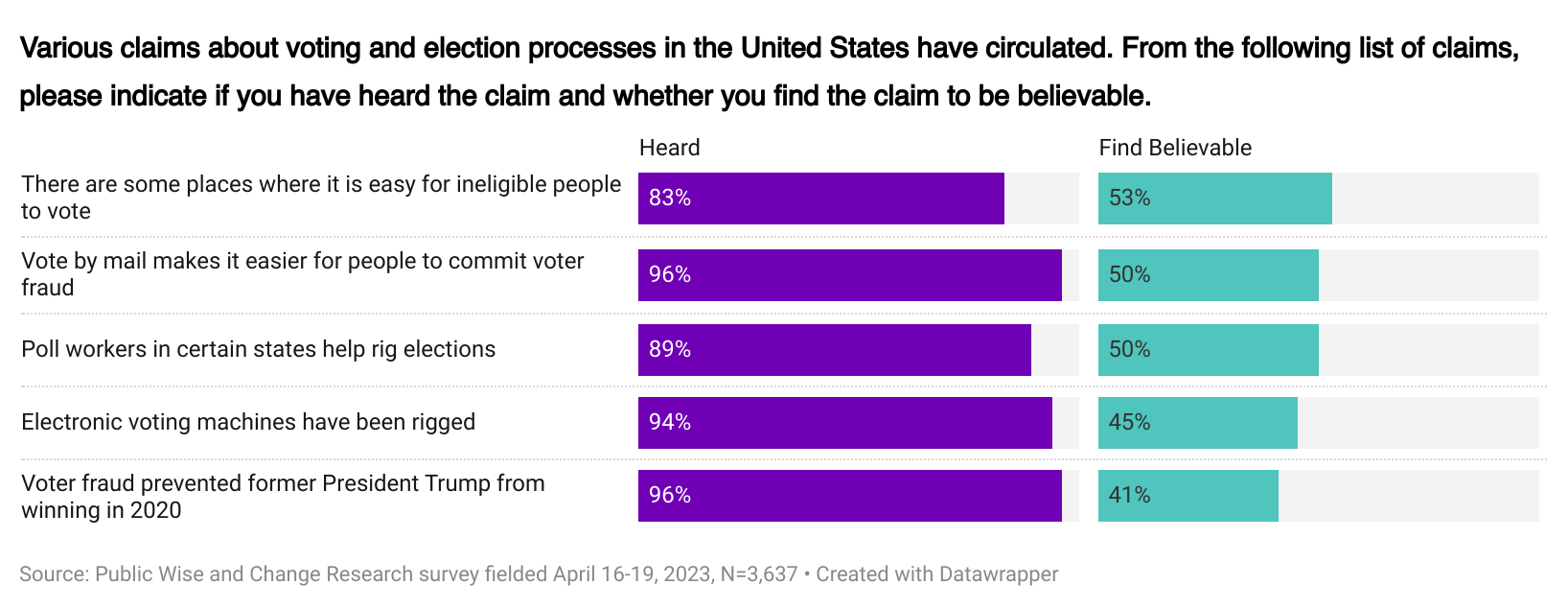

We asked about five common election denier claims. We found exposure to election denial rhetoric is widespread, but belief in election denial rhetoric is split along ideological lines.2

Virtually all registered voters report having heard election denier rhetoric of some kind, but some claims appear to be more believable than others. Slightly over half (53%) of all respondents found it believable that there are places where it is easy for ineligible people to cast ballots, and 50% of all respondents found it believable that vote by mail makes it easier for people to commit fraud and that poll workers in certain states help rig elections.

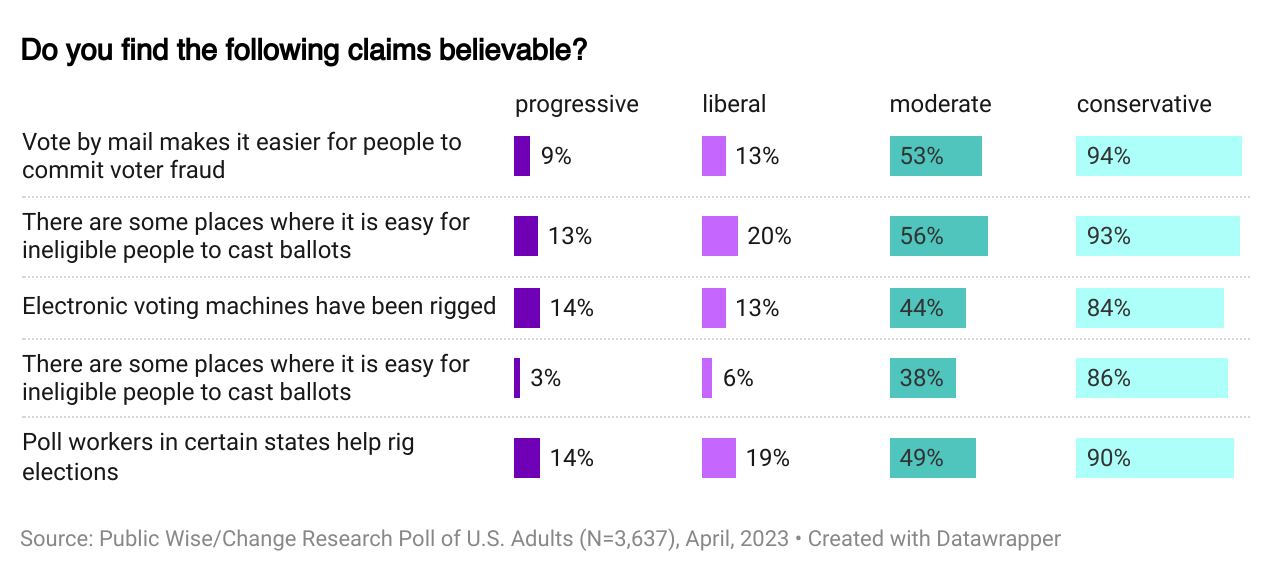

Most conservatives find all election denier claims believable. Moderates are more likely to believe each claim compared to progressives, but less likely to believe them compared to conservatives.

A small but substantial share of liberals and progressives found some election denier claims to be believable. 13% of progressives and 20% of liberals find the claim that there are some places where it is easy for ineligible people to cast ballots to be believable.

Another 14% of progressives and 19% of liberals find it believable that poll workers in certain states help rig elections.

What are the defining characteristics of election deniers?

Registered voters have largely heard election denial rhetoric and the majority report they are less likely to vote for a candidate who has been characterized as an election denier, but do they have a common understanding of what it means to be an election denier? It seems like the answer is no. This may reflect a combination of factors, including the fact that across plenty of media coverage referring to election deniers the term is being used to describe many different behaviors with very little overlap across sources and that election deniers themselves have engaged in many combinations of these behaviors.

In their definition of election deniers, The Washington Post includes people who questioned Biden’s victory (e.g. Belief in the Big Lie of election fraud), opposed counting electoral votes, and sought to overturn the 2020 election.

Many of these characteristics correspond to a variety of other anti-democratic views, but the full range of beliefs and behaviors the public associates with those labeled as election deniers remains unclear.

For example, election deniers have been broadly characterized as believing in and spreading conspiracy theories and false claims about voter fraud. But they also cast doubt on legitimate voting options such as vote by mail, claiming – without evidence – it is a mechanism for widespread voter fraud. These claims about voter fraud are then used to justify support for voter suppression legislation.

In fact, the Brennan Center for Justice released a “playbook” of election denier candidates, pointing to a number of strategies they tend to employ, including spreading misinformation, efforts to suppress votes, threatening poll workers, discrediting voting machines, and undermining vote-by-mail.

Given the scope of election denier characteristics, their tendency to support voter suppression, and the conspicuousness of their claims in the wider media landscape, we wanted to know whether any of these other descriptions – above and beyond denying the 2020 election results – are salient for voters as accurate portrayals of election denier candidates.

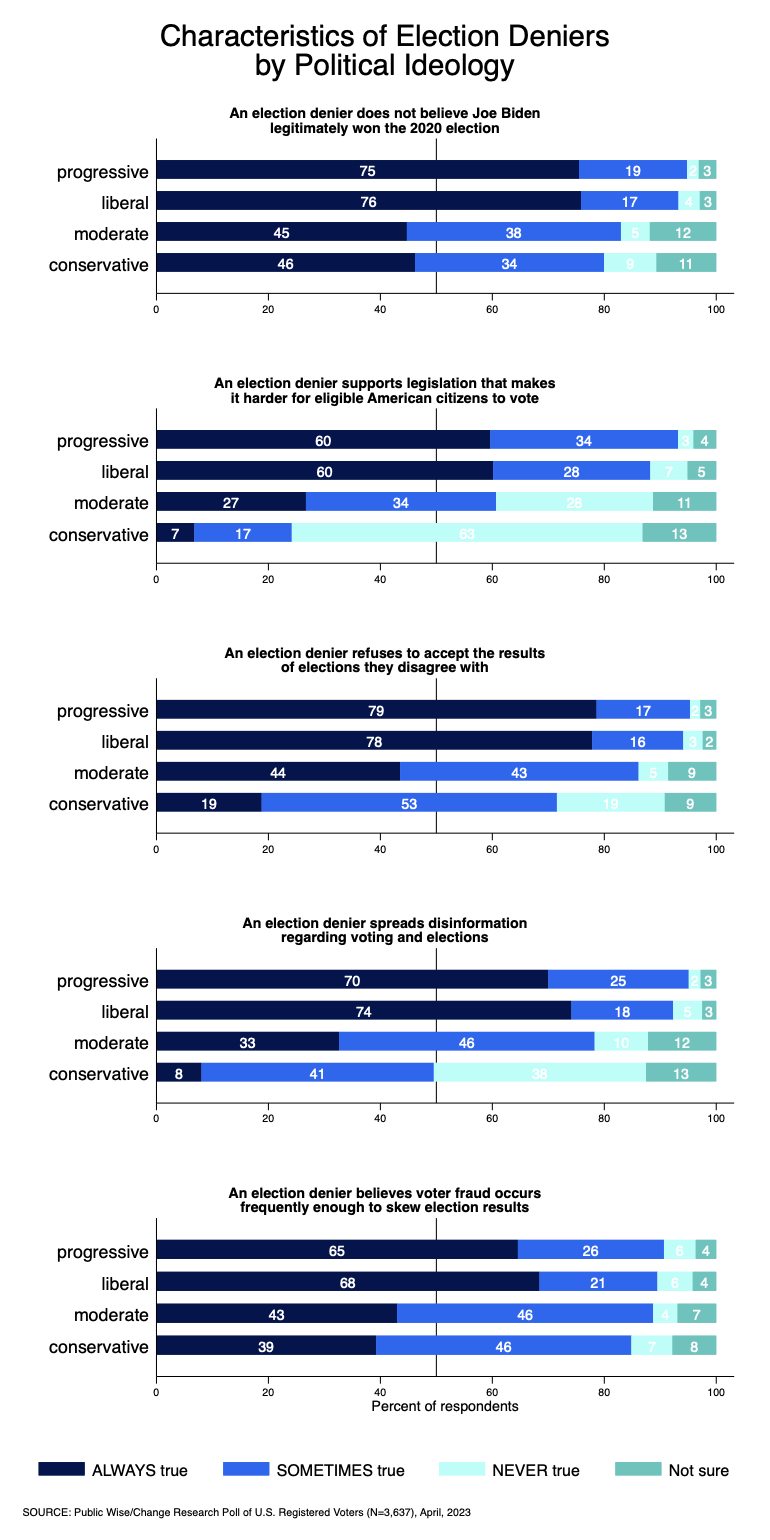

In our survey, we asked participants to assess whether the following five statements about someone labeled an election denier are always true, sometimes true, never true, or not sure:

- An election denier does not believe Joe Biden legitimately won the 2020 election

- An election denier supports legislation that makes it harder for eligible American citizens to vote

- An election denier refuses to accept the results of elections they disagree with

- An election denier spreads disinformation regarding voting and elections

- An election denier believes voter fraud occurs frequently enough to skew election results

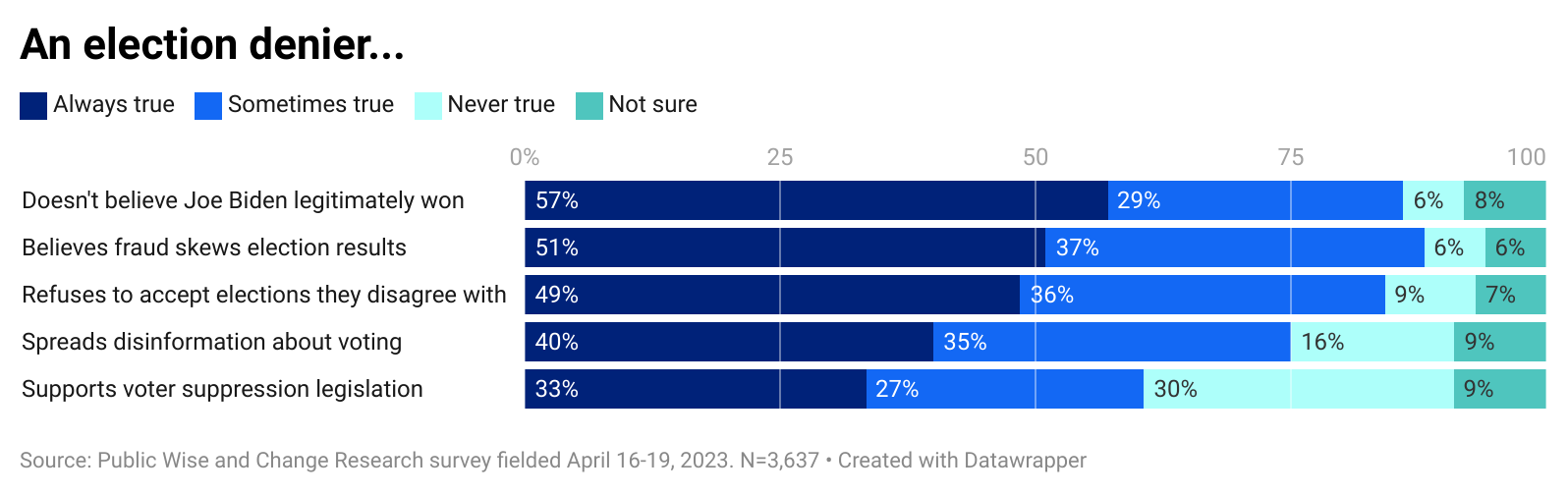

Slightly more than half of registered voters claim two characteristics are “always true” of election deniers: that they do not believe Joe Biden legitimately won the 2020 election (57%) and they believe voter fraud happens frequently enough to skew election results (51%).

The extent to which respondents felt each of the five descriptors applied to election deniers varied widely by partisan ideology.3 Between 60-78% of liberals and progressives responded “always true” for all items, while roughly half or less of all conservative respondents said “always true” for all items. Similar to views on accountability for January 6th, these wide ideological splits are obscured by the overall average.

Despite being a common campaign message of election denier candidates, only 65% of progressives and 68% of liberals said it is “always true” that election deniers believe voter fraud occurs frequently enough to skew election results, compared to 43% of moderates and 39% of conservatives.

The description garnering the largest share of progressives and liberals claiming it is “always true” is that election deniers refuse to accept the results of elections they disagree with. On the other hand, there was no one election denier description that was “always true” for the majority of conservatives. The statement that election deniers do not believe Biden legitimately won in 2020 came closest with 46% of conservatives saying it is always true.

There is also ideological disagreement about the extent to which election deniers support voter suppression legislation: 60% of both liberals and progressives said it is “always true” that election deniers support legislation that make it harder for eligible citizens to vote, while 63% of conservatives said this is “never true” of election deniers. 27% of moderates thought this is always true of election deniers, while another 28% thought it is never true.

These results show that while most registered voters have heard some form of election denial rhetoric, there is not one clear definition of election denier that resonates with the American public, and the characteristics that ring most true differ across ideological lines. Despite this lack of clear definition, the majority of registered voters still said they were less likely to vote for an election denier.

Looking ahead: clearly communicate the election denier agenda and how it harms democracy

Although election denialism was a decisive issue of the 2022 midterms, our findings suggest that registered voters do not have a consistent picture of what an election denier looks like. In our survey, barely more than half (57%) said that it is always true that an election denier is someone who does not believe that Biden legitimately won the 2020 election, despite many news organizations widely agreeing on that as a condition for labeling someone an election denier.4

While the 2022 elections are over, the broader election denial movement is not. At the top of the ticket, Trump has already entered the 2024 race with early polling suggesting he leads other candidates by a wide margin. And he’s not the only election denier running for office. Many election deniers currently in office will be running for reelection and many others will try to take new positions, including those that directly oversee election administration.

Moreover, in the nearly three years since the 2020 election and insurrection that followed, the election denial movement and its implications have grown far beyond the lie that Trump won the 2020 election. Much of the rhetoric used to push this lie relied on false claims about the security of US elections, including lies about voter fraud, vote by mail, poll workers, electronic voting machines, and ballot counting procedures. The post-2020 election denier playbook builds on these lies with an agenda designed to limit voting by mail, complicate the counting of votes with things like hand count requirements and audits, and change who controls the certification of results. These lies have also been used to justify voter suppression legislation, even in states like Georgia where Republican officials defied Trump’s demands to find him the votes he needed to win the 2020 election.

As we move closer to 2024, the urgency of communicating these goals – and the harm that comes with them – continues to grow. Our data suggest that, in addition to many not thinking it is always true that election deniers reject Biden’s legitimate win in 2020, many Americans also remain unaware of other key features of election denialism. Only about half said it is always true that election deniers believe fraud skews election results (51%) and that election deniers refuse to accept the results of elections they disagree with (49%). Only 40% said it’s always true that election deniers spread disinformation about voting, and even fewer, 33%, said it’s always true that election deniers support voter suppression legislation.

The upside for democracy is that election deniers and the key claims of their movement remain unpopular among many Americans. While their rhetoric is widespread in the sense that almost everyone has heard their lies about elections and voting, belief in these lies is not widespread, especially among Democrats, left-leaning Independents, and a sizable share of moderates. Many also say they are much less likely to vote for someone who has been widely characterized as an election denier, including 92% of progressives, 83% of liberals, and 48% of moderates.

However, because many Americans remain unfamiliar with the key provisions of the election denier platform, there is an opportunity for defenders of democracy to broaden the narrative beyond denial of the 2020 election to encompass the bigger story of how these election denial behaviors fit into a broad threat to our democratic systems, particularly by explicitly connecting the lies about elections and voting to the candidates that seek to be in positions of power, especially those directly overseeing election administration.

No comments:

Post a Comment