Larry Motuz pointed this gem out as something of interest. It’s about wealth inequality, ownership of corporations and how wealth and power flows and accumulates:

Stocking Up on Wealth … ConcentrationSpeaking of competition and losers, Ronald Reagan set the tone of the neoliberal era when, in 1981, he fired 11,000 striking air-traffic controllers. The message? Workers were losers who would be subjected to the discipline of competition. Reagan called it ‘morning in America’. But really, it was ‘morning for American big business’.

Today, we are well into the next-day’s hangover, and we know how the party played out. For workers, it was a disaster. But for the rich, it was an incredible boon. Wealth didn’t trickle down so much as it got catapulted up. The result, as Figure 1A shows, was a relentless rise in the concentration of American wealth.

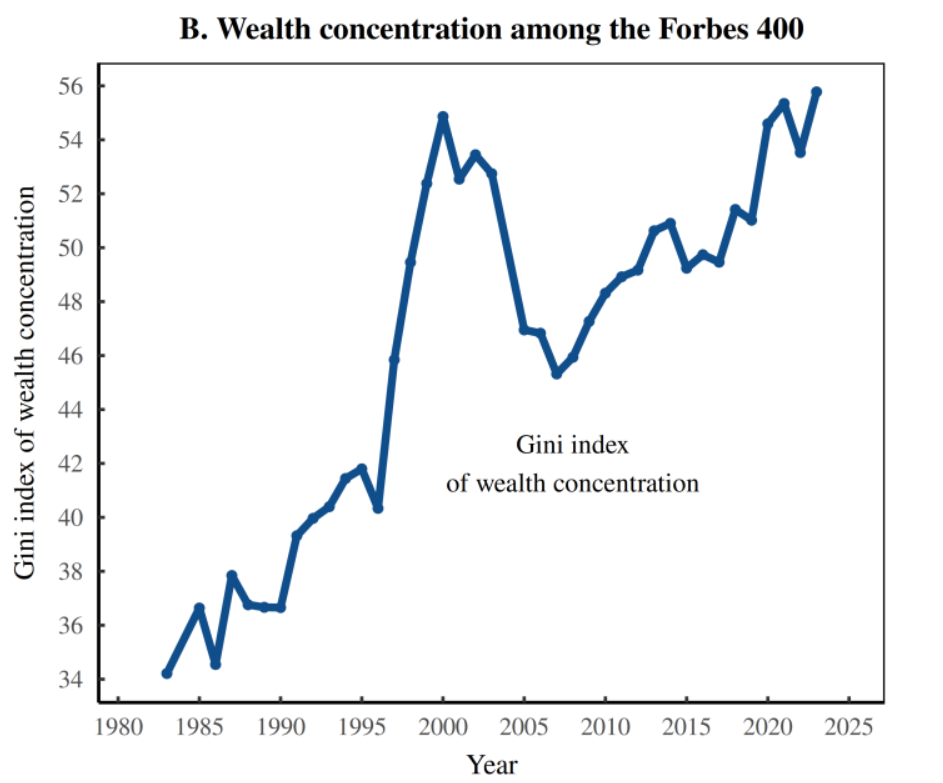

Interestingly, as wealth got catapulted from the poor to the rich, it also got transported from the mega rich to the supremely rich. This is the story told by Figure 1B. Here, I’ve focused on the richest Americans — the folks who grace the Forbes 400 list. Even here, among the upper crust of elites, wealth has grown more concentrated. Why?

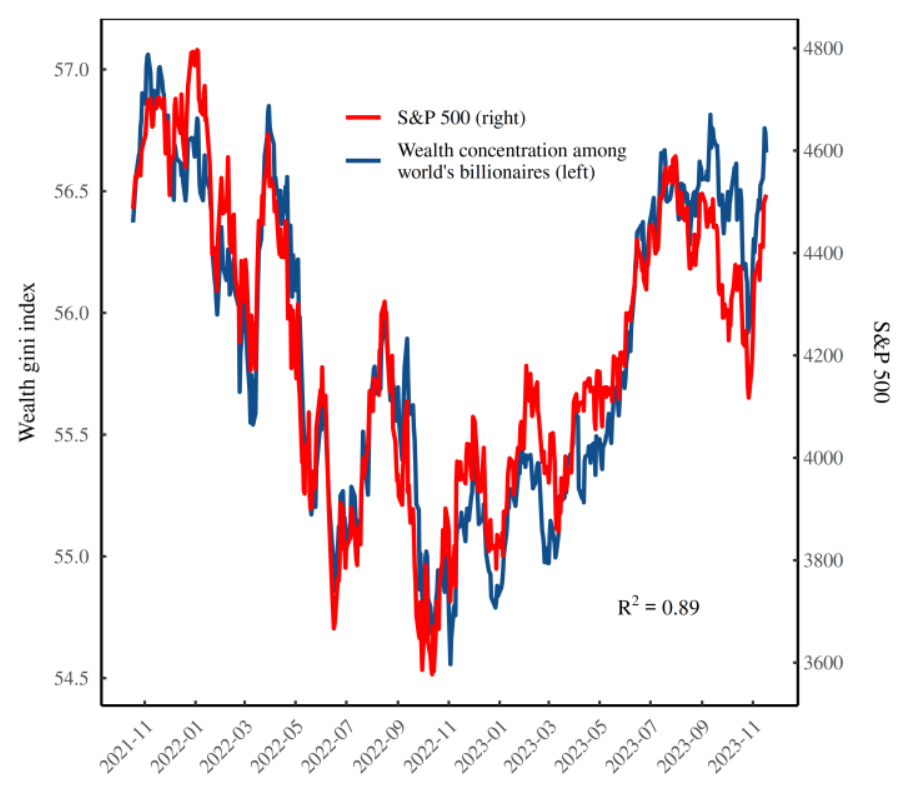

As you’ll see, the culprit seems to be the stock market.The message is that billionaire wealth is both spectacularly large and spectacularly concentrated. .... Something is driving billionaire wealth concentration up and down. What could it be?The stock market drives billionairewealth concentration

The stock-market average seems to ‘know’ about something that it shouldn’t. Why?

.... It happens when growth is driven by inequality. .... the S&P 500 index (an average) is connected to levels of elite wealth concentration (a form of spread). But this connection only makes sense if the S&P 500 is an (unwitting) indicator of stock-market inequality..... what I’m calling ‘growth through inequality’ — explains our stock-market results. .... the S&P 500 index (an average) is connected to levels of elite wealth concentration (a form of spread). .... in simple terms, the S&P 500 tracks the total market capitalization of the 500 largest US firms.

.... firms that are giant companies like Apple, Microsoft, Google and Amazon — four corporations that have a combined market capitalization of about $5.9 trillion. .... [those huge] firms account for about a sixth of the value of the entire S&P 500. So if their stock rises, it will buoy the whole S&P 500 index. But this buoyancy isn’t really ‘growth’; it’s an artifact of corporate concentration — rich firms getting richer.

.... we’ve got evidence that the S&P 500 is an unwitting indicator of US corporate concentration. And it’s not because S&P analysts tried to make that happen. (They didn’t.) It’s because historically, an important part of (apparent) stock-market growth is simply the richest firms getting richer.

To the owners go the spoils

So what happens as rich firms get richer? Well, the rich owners of these firms also get richer. .... the concentration of corporate wealth should beget the concentration of individual wealth. So does it? At least in the United States, the answers seems to be yes. .... To the richest owners go the spoils of oligopoly.The concentration of corporate wealthbegets the concentration of individual wealth.At this point we’ve got some fairly incendiary evidence. The ‘crime’ of elite wealth concentration seems to be tied directly to corporate oligarchy. But .... let’s consider the testimony of the defense’s expert witnesses. I’m talking, of course, about neoclassical economists.Ostensibly, neoclassical economists love competitive markets and hate monopoly. But beginning in the 1980s, a weird thing happened; economists at the University of Chicago started to argue that despite lacking competition, monopolies could still be ‘efficient’. Their reasoning was that if monopolists actually behaved badly, they would be undercut by competitors, and their monopoly would be undone. Therefore, if a monopoly exists, it must be because the monopolist is doing what the market wants.

Now the logic here is torturous. We’re positing imaginary competition to justify a lack of real-world competition. But then again, neoclassical economists have never let the real world get in the way of their imaginations. And in this case, the goal of the imaginary theorizing was always obvious: it was designed get government out of the way and allow big corporations to purchase their way to power.

Backing up a bit, politicians are rarely incensed when a big corporation builds more factories. So in that sense, the government is not opposed to big companies getting bigger. But from a corporate vantage point, factory building is a less-than-ideal route to bigness. The problem is simple: if everyone builds more factories, it leads to ‘free run of production’ (Thorstein Veblen’s term) which then collapses profits. So savvy corporations are always looking for a better route to power. And that better route is to buy instead of build.

The buy-not-build tactic is hardly rocket science. As Jonathan Nitzan and Shimshon Bichler observe, when you buy your competitor, you solve two problems at once: you accumulate power and reduce your competition. The difficulty, though, is that this buy-not-build tactic has the appearance of being a blatant power grab. So there’s the risk that an entrepreneurial government might get in the way.

That’s where Chicago-school theorists come in. Starting in the 1980s, they successfully preached an ideology that got the government out of the way. The net result is the modern corporate landscape, forged in large part by a string of government-approved corporate acquisitions.

Tech monopolist Google has been a prime benefactor of this buy-not-build tactic. As Cory Doctorow notes, “Google didn’t invent its way to glory — it bought its way there.” He continues:Google’s success stories (its ad-tech stack, its mobile platform, its collaborative office suite, its server-management tech, its video platform …) are all acquisitions.

The same strategy holds for most of today’s corporate oligarchies. Their tentacles have largely been bought, not built. On this front, the numbers don’t lie: the consolidated corporate landscape of the 21st century was forged by a massive, neoliberal wave of mergers and acquisitions.

To quantify the scale of mergers and acquisitions, we’ll turn to an index called the buy-to-build ratio. As the name suggests, the buy-to-build ratio measures the corporate proclivity for buying other companies instead of building new capacity. Created by Jonathan Nitzan and Shimshon Bichler (and first published in 2001), the buy-to-build ratio takes the value of corporate mergers and acquisitions and divides them by the value of greenfield investments. The greater this buy-to-build ratio, the more that corporations are buying (and not building) their way to power.

As I’ve alluded, the neoliberal era saw a massive wave of corporate mergers and acquisitions. As a result, from 1980 to 2000, the US buy-to-build ratio jumped nearly tenfold. And guess what accompanied this acquisition wave. That’s right … a sharp rise in corporate concentration. .... over the last forty years, big corporations have been buying their way to consolidated power.

One of the (few) nice things about living in an era of concentrated corporate power is that modern plutocrats are brash enough to speak plainly about their ambitions. Forget the arcane language wielded by Chicago-school economists. Today’s plutes — men like Peter Thiel — say the quiet part out loud. If you want to ‘capture lasting value’, Thiel proclaims, ‘look to build a monopoly’. Or in mantra form, ‘competition is for losers’. (emphasis added)

John D. Rockefeller would be proud.

Speaking of Rockefeller, did you know that he was one of the principle funders of the University of Chicago? Ironic, isn’t it. Rockefeller, like Thiel, spoke openly about his pursuit of power and personal enrichment. So if, during Rockefeller’s life, someone had connected elite wealth concentration to corporate consolidation, the reaction would have been “Well, that’s obvious.”

Fast forward to the 1980s and the connection became not-so obvious, at least to economists. And that’s thanks in large part to Rockefeller’s Chicago-school investment, which pumped out decades worth of pro-oligarch propaganda.

Today, we’ve come full circle. Billionaires like Peter Thiel are so hubristic that they speak brazenly about their pursuit of power, laying bare their inner robber baron. The upshot to this plute bravado is that few people will be surprised by the straight line that connects corporate oligarchy with the concentration of elite wealth.

That's sobering. Buy-don’t build is what got most of America’s major plutocrats much or most of their vast wealth and power. And if you look at it, anti-democracy authoritarianism is inherent in buy-don’t build dogma. Put another way, there is fierce competition for two things that tend to go together, wealth and power. The twin tendencies are (i) with wealth comes power, and (ii) with power comes wealth. What gets in the way of accumulating wealth? Regulations, government and the public interest or general welfare (civil liberties, transparent, honest government, etc.).

This is a very plausible explanation for the tactics and dogma that mostly animates America’s authoritarian radical right brass knuckles capitalist elites. That is just as scary as the tactics and dogma that animate America’s authoritarian radical right Christian nationalist elites. It’s a marriage made in hell for average people, democracy, the rule of law and civil liberties, but it’s made in heaven for the elites.

No comments:

Post a Comment