CONTEXT

Ladies and germs, we have another potential rut roh on our hands. 🥺 This one is about climate, but my interest in this is the human mind first, but also the possibility that the climate situation is worse than consensus expert opinion would have us believe. If I recall right, I first raised that possibility in 2017 or 2018 on the old, now extinct Disqus community platform. FWIW, my blog then was called Biopolitics and Bionews. The argument was simple to climate science deniers who claimed that climate prediction models overstated the severity of the climate issue because the models were inaccurate. Well if the models overstated the case due to being inaccurate, why can't they be inaccurate due to understating the situation. No one on the climate science-denier side ever responded to me convincingly with data. Not even once.

In the ensuing years, evidence of understatement kept accumulating but was downplayed by the clueless MSM and flat out denied by the pro-pollution radical right authoritarian propaganda Leviathan.

This tempest in the teapot is between science communicator Sabine Hossenfelder and climate scientists Zeke Hausfather and Andrew Dessler.

To keep the complexity simple (sort of), I extract and translate this from a recent Steve Novella post at Neurologica blog entitled Climate Sensitivity and Confirmation Bias. Novella is a practicing medical doctor and self-professed science communicator and science skeptic. dcleve, an occasional commenter here, thinks Novella is a crackpot pseudoscientist when it comes to his attitude toward psi research, dualism, free will and consciousness. IMHO, he has a point. Outside of that ongoing kerfuffle, Novella strikes me as a simple guy just working hard to put food on the table for the young ’uns. He is an assistant professor of neurology at the Yale school of medicine, so he’s a regular lunch pail ’n coffee thermos working stiff just like the rest of us. (full professors get better lunches with martinis)

Novella focuses on the Hossenfelder vs. Hausfather and Dessler debate about the hot model problem. He is looking for the nuance and subtlety of thinking and reasoning when experts debate and disagree. In addition to finding out I am wrong, that is a major thing I look for when I disagree with people here. I like looking at how minds in disagreement work.

Confirmation bias, the hot climate model problem

and other whatnot

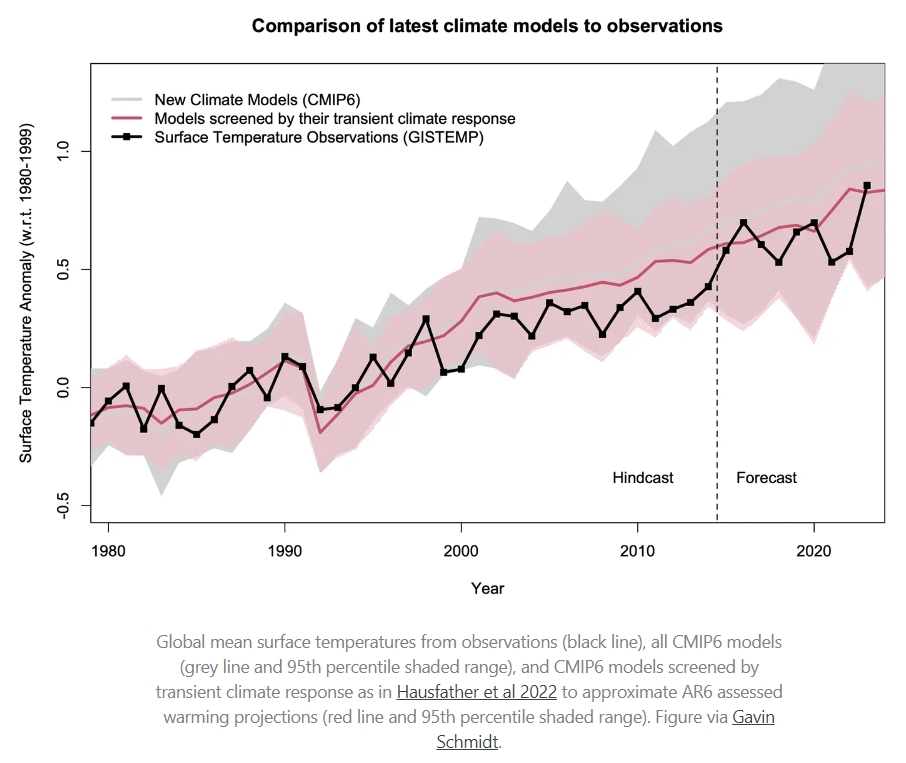

Communicator Hossenfelder posted a 22 minute video, I wasn't worried about climate change. Now I am, which focused on some recent climate modeling studies that suggest the climate change situation is significantly worse that consensus expert opinion had believed. That data is outside the usual range of warming that various other models have predicted. So the question is, should the data be taken as accurate or as a statistical fluke? A couple of weeks later Hossenfelder posted a shorter video (9 minutes), I Was Worried about Climate Change. Now I worry about Climate Scientists, that reflects how she sees climate science experts after the response to her hot model video.

We all can see where this is going, South. Hossenfelder's second video was prompted by what Hausfather and Dessler posted at The Climate Brink, a piece entitled Revisiting the hot model problem:

In a recent YouTube video, the physicist and science communicator Sabine Hossenfelder brought up the “hot model problem” that one of us (ZH) addressed in a Nature commentary last year, and suggested that it might be worth revisiting in light of recent developments.While 2023 saw exception levels of warmth – far beyond what we had expected at the start of the year – global temperatures remain consistent with the IPCC’s assessed warming projections that exclude hot models, and last year does not provide any evidence that the climate is more sensitive to our emissions than previously expected.

To frame my take on this debate a bit, when thinking about any scientific debate we often have to consider two broad levels of issues. One type of issue is generic principles of logic and proper scientific procedure. These generic principles can apply to any scientific field – P-hacking is P-hacking, whether you are a geologist or chiropractor. This is the realm I generally deal with, basic principles of statistics, methodological rigor, and avoiding common pitfalls in how to gather and interpret evidence.

The second relevant level, however, is topic-specific expertise. Here I do my best to understand the relevant science, defer to experts, and essentially try to understand the consensus of expert opinion as best I can. There is often a complex interaction between these two levels. But if researchers are making egregious mistakes on the level of basic logic and statistics, the topic-specific details do not matter very much to that fact.

What I have tried to do over my science communication career is to derive a deep understanding of the logic and methods of good science vs bad science from my own field of expertise, medicine. This allows me to better apply those general principles to other areas. At the same time I have tried to develop expertise in the philosophy of science, and understanding the difference between science and pseudoscience. [remember dcleve!]In her response video Hossenfelder is partly trying to do the same thing, take generic lessons from her field and apply them to climate science (while acknowledging that she is not a climate scientist). Her main point is that, in the past, physicists had grossly underestimated the uncertainty of certain measurements they were making (such as the half life of protons outside a nucleus). The true value ended up being outside the earlier uncertainty range – h0w did that happen? Her conclusions was that it was likely confirmation bias – once a value was determined (even if just preliminary) then confirmation bias kicks in. You tend to accept later evidence that supports the earlier preliminary evidence while investigating more robustly any results that are outside this range.Here is what makes confirmation bias so tricky and often hard to detect. The logic and methods used to question unwanted or unexpected results may be legitimate. But there is often some subjective judgement involved in which methods are best or most appropriate and there can be a bias in how they are applied. It’s like P-hacking – the statistical methods used may be individually reasonable, but if you are using them after looking at data their application will be biased. Hossenfelder correctly, in my opinion, recommends deciding on all research methods before looking at any data. The same recommendation now exists in medicine, even with pre-registration of methods before collective data and reviewers now looking at how well this process was complied with.

So Hausfather and Dessler make valid points in their response to Hossenfelder, but interestingly this does not negate her point. Their points can be legitimate in and of themselves, but biased in their application. The climate scientists point out (as others have) that the newer hot models do a relatively poor job of predicting historic temperatures and also do a poor job of modeling the most recent glacial maximum. That sounds like a valid point. Some climate scientists have therefore recommended that when all the climate models are averaged together to produce a probability curve of ECS that models which are better and predicting historic temperatures be weighted heavier than models that do a poor job. Again, sounds reasonable.

But – this does not negate Hossenfelder’s point. They decided to weight climate models after some of the recent models were creating a problem by running hot. They were “fixing” the “problem” of hot models. Would they have decided to weight models if there weren’t a problem with hot models? Is this just confirmation bias?

None of this means that there fix is wrong, or that the hot models are right. But what it means is that climate scientists should acknowledge exactly what they are doing. This opens the door to controlling for any potential confirmation bias. The way this works (again, generic scientific principle that could apply to any field) is to look a fresh data. Climate scientists need to agree on a consensus method – which models to look at, how to weight their results – and then do a fresh analysis including new data. Any time you make any change to your methods after looking at the data, you cannot really depend on the results. At best you have created a hypothesis – maybe this new method will give more accurate results – but then you have to confirm that method by applying it to fresh data.

Perhaps climate scientists are doing this (I suspect they will eventually), although Hausfather and Dessler did not explicitly address this in their response.

It’s all a great conversation to have. Every scientific field, no matter how legitimate, could benefit from this kind of scrutiny and questioning. Science is hard, and there are many ways bias can slip in. It’s good for scientists in every field to have a deep and subtle understanding of statistical pitfalls, how to minimize confirmation bias [and hindsight bias and other biases!] and p-hacking, and the nature of pseudoscience.

There are 4 basic choice when faced with a mess like this. Mostly or completely accept it, mostly or completely deny it, not care/unaware or confused/unsure. The latter two groups are typically outcome-determinative.

Writing this post was really fun for me. This is at the heart of how I see the human condition, politics, ideology, the human mind and mental freedom vs. entrapment. Don't you just love bickering experts, especially ones in different areas of expertise ? I sure do!

Q: Is this creepy wonkiness, good stuff, or something else, e.g., TL/DR & where is the popcorn?

No comments:

Post a Comment