It’s Not Just WagesRetailers Are Mistreating Workers in a More Insidious WayI got a job at a big-box store near the Catskills in New York, where I live. I was on the team that unloaded the truck of new merchandise each morning at 4 a.m.

We were supposed to empty the truck in under an hour. Given how little we made — I was paid $12.25 an hour, which I was told was the standard starting pay — I was surprised how much my co-workers cared about making the unload time. They took a kind of bitter pride in their efficiency, and it rubbed off on me. I dreaded making a mistake that would slow us down as we worked in tandem to get between 1,500 and 2,500 boxes off the truck and sorted onto pallets each morning. When the last box rolled out of the truck, we would spread out in groups of two or three for the rest of our four-hour shift and shelve the items from the boxes we’d just unloaded.

Most of my co-workers had been at the store for years, but almost all of them were, like me, part time. This meant that the store had no obligation to give us a stable number of hours or to adhere to a weekly minimum. Some weeks we’d be scheduled for as little as a single four-hour shift; other weeks we’d be asked to do overnights and work as many as 39 hours (never 40, presumably because the company didn’t want to come anywhere close to having to pay overtime).

The unpredictability of the hours made life difficult for my co-workers — as much as, if not more than, the low pay did. On receiving a paycheck for a good week’s work, when they’d worked 39 hours, should they use the money to pay down debt? Or should they hold on to it in case the following week they were scheduled for only four hours and didn’t have enough for food?

Many of my co-workers didn’t have cars; with such unstable pay, they couldn’t secure auto loans. Nor could they count on holding on to the health insurance that part-time workers could receive if they met a minimum threshold of hours per week. While I was at the store, one co-worker lost his health insurance because he didn’t meet the threshold — but not because the store didn’t have the work. Even as his requests for more hours were denied, the store continued to hire additional part-time and seasonal workers.

My co-workers struggled to supplement their income elsewhere, because the unstable hours made it hard to work a second job. If we wanted more hours, we were advised to increase our availability. Problem is, it’s difficult to work a second job when you’re trying to keep yourself as free as possible for your first job.

No wonder my co-workers cared so much about the unload time: For those 60 minutes, they could set aside such worries and focus on a single goal, one that may have been arbitrary but was largely within our shared control and made life feel, briefly, like a game that was winnable.

It’s not just Walmart. Target, TJX Companies, Kohl’s and Starbucks all describe their median employee, based primarily on salary and role, as a part-time worker. Many jobs that were once decent — they didn’t make workers rich, but they were adequate — have quietly morphed into something unsustainable.

One of the most surprising aspects of this movement toward part-time work is how few white-collar people — including economists and policy analysts — have seemed to notice or appreciate it.

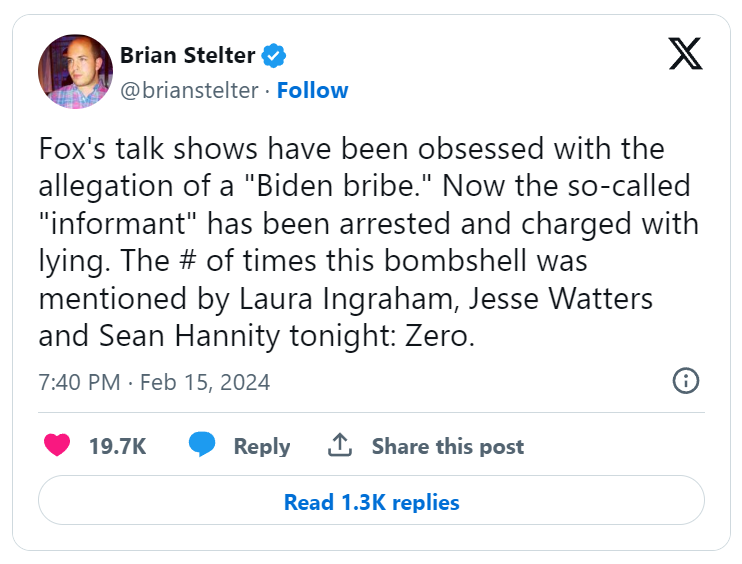

Sinclair’s recipe for TV news: Crime, homelessness, illegal drugs

The local news powerhouse, whose chairman recently bought the Baltimore Sun, focuses on fear in broadcasts that often align with Donald Trump’s view of citiesEvery year, local television news stations owned by Sinclair Broadcasting conduct short surveys among viewers to help guide the year’s coverage. A key question in each poll, according to David Smith, the company’s executive chairman: “What are you most afraid of?”On Sinclair’s growing nationwide roster of stations, the editorial focus reflects Smith’s conservative views and plays on its audience’s fears that America’s cities are falling apart, according to media observers, Smith associates, and current and former staffers who spoke on the condition of anonymity to discuss internal company matters.

Smith, an enthusiastic supporter of Republican presidential front-runner Donald Trump who has built Sinclair into one of the largest television station operators in the country, purchased the Baltimore Sun last month. In a private meeting with the Sun’s journalists, he urged them to emulate coverage at the local Sinclair station, Fox45, which in 2021 produced a documentary titled simply “Baltimore Is Dying.”

Sinclair’s local network of 185 stations across the country makes it an influential player in shaping the views of millions of Americans, especially at a time when local newspapers are rapidly being gutted — or closed altogether.

As Sinclair increasingly fills the void, it offers its viewers a perspective that aligns with Trump’s oft-stated opinion that America’s cities, especially those run by Democratic politicians, are dangerous and dysfunctional.

Smith did not respond to requests for an interview. A spokeswoman for Sinclair said that the company’s stations “are committed to accountability reporting, exposing issues within the community, and seeking answers and solutions for viewers.” She added, “Our aim is to help create safer communities, improve public education and the overall quality of life, which are universal, nonpartisan concerns.”

In a recent survey conducted by a panel of experts specializing in the American presidency, President Biden was ranked the 14th-best president, while his likely 2024 presidential opponent former President Trump found himself at the very bottom of the list.

I guess the court said those documents had meaning. Who would have thunk? Certainly not Mr. Hitt.